Special delivery: Sign up for the free Marlin email newsletter. Subscribe to Marlin magazine and get a year of highly collectible, keepsake editions – plus access to the digital edition and archives.

Considered by many to be ultimate gamefish, blue marlin and sailfish are found worldwide in both tropical and subtropical waters. Noted for their high-speed runs, strong fights, and aerial acrobatics, these are some of the most sought-after fish in offshore angling. Recreational fishing for these charismatic species continues to increase around the world, providing considerable economic benefit, and prompting many countries to mandate catch-and-release practices for perceived conservation.

For the angler, a fight with a billfish consists of a fast-paced, high-energy battle of wills that hopefully culminates in a safe release, some high-fives, and a quick redeployment of the spread for the next one. But for the fish, this is a fight for its life. It uses a tremendous amount of energy doing so, and it is precisely those high-speed runs and aerial acrobatics that beg the question: How long does it take them to physically recover from that fight after being released?

Survival of the Fittest

Previous research into the survival of several billfish, depending on the species, has shown that approximately 86 percent survive to fight another day after being released. This is good news for anglers, and suggests that recreational catch-and-release is—and continues to be—a successful management practice to conserve billfish populations. However, how the behavior of the billfish changes and how long it takes for the fish to recover have received far less attention, and could have important implications.

For example, if many fish are caught during a spawning aggregation but then fail to spawn after being released, that would greatly reduce the reproductive output of that population. Reproductive output is an important term for estimating population sizes, and previous studies examining recovery times have produced surprisingly different results (a few hours versus several weeks), depending on the post-release tracking method used. With robust information on what the fish do after release, what temperatures and oxygen levels they need to recover, and accurate information on their recovery dynamics, it might be possible to predict how many fish will not survive a fight with a fisherman based on the environmental conditions of where they are caught. Therefore, understanding how fish behave and how long it actually takes them to recover will add an important component to the management and conservation of billfish fisheries around the world.

Recovery-Tracking Technology

Using a high-resolution technology that had never before been applied to a billfish, a new research study recently published in ICES Journal of Marine Science set out to answer the question of post-release behavior and recovery time for blue marlin and sailfish caught offshore of one of the premier fishing locations in the world: Panama’s Tropic Star Lodge. The technology, called an inertial measurement unit, is a device that integrates multiaxes accelerometers, gyroscopes, magnetometers, and other sensors to provide estimation of an object’s orientation and movement in space.

This might sound confusing, but nearly all modern electronics use an IMU. Your cellphone tells your screen to rotate when you turn the device sideways, knows what the cellphone’s compass heading is, and helps your smartwatch count how many steps you take and how many calories you burn throughout the day.

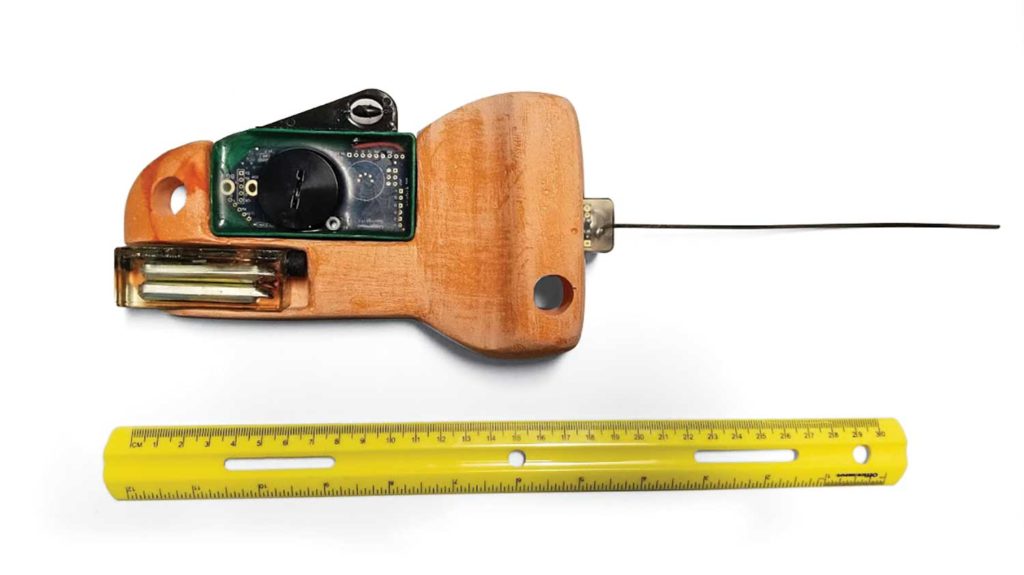

In the study, many other sensors were also used after catching a blue marlin or a sailfish on traditional recreational trolling gear: A custom-built tag package combined an IMU with depth, temperature, oxygen and speed sensors, a video camera, and a satellite transmitting beacon. This tag was quickly affixed to the fish’s body with two points of attachment near the shoulder just below the dorsal fin, and the fish was released. The multisensor tag provided a means to gather an exquisitely detailed picture of fish movement and behavior, and particularly how those behaviors changed over time. However, unlike previous data-archival tags that transmit a variable portion of the information they gather to satellites, IMU tags must be physically recovered after they come off the fish due to the ultra-high resolution—up to 100 measurements per second—of the data being collected. Once the tag releases from the fish some 24 to 72 hours later, researchers must track down the floating tag using signals from the satellite transmitting beacon in the tag package.

Due to the high-resolution nature of the data, virtually every movement the fish makes is recorded. For example, how fast and hard the fish’s tail is moving back and forth, if the fish rolls to the left or right, if its bill is pointed up or down, and what direction the fish is headed are all recorded by the IMU. This information, along with depth, temperature, water oxygen levels, and the speed of the fish were all statistically analyzed to determine how it changed over time, estimating how long it took until the behaviors leveled off to a steady pattern, indicating that the fish had recovered.

Read Next: The so-called 30 by 30 movement could do significant harm to sport fishing. Learn more about it here.

Results

If you’ve caught both blues and sails, you know that sailfish fights are exciting but relatively short-lived compared with a blue marlin. The average fight time for a sailfish during the study was about seven minutes, compared with roughly 45 minutes for an average blue marlin fight. Because of this, it should come as no surprise that blue marlin take longer to recover. Interestingly, immediately after you release a blue marlin, it dives to the thermocline depth and will remain there for an extended period of time, typically somewhere between one and 10 hours. The study found that the length of this period largely depends on how long the fight was. While they are down there, they are swimming faster than normal and beating their tail harder and faster than normal. Sailfish, on the other hand, do not always dive after being released, but they do beat their tail harder and faster than normal.

Because marlin and sailfish have to continuously swim to breathe, it is likely that this faster-than-normal swimming behavior is a way for them to increase the amount of oxygen moving over their gills, facilitating recovery. Similar to humans huffing and puffing after a workout to increase the amount of oxygen delivered to our tissues, these fish have to swim harder to create the same effect.

In the study, individual blue marlin recovered anywhere from three to 16 hours after release, with an average of nine hours, and individual sailfish recovered anywhere from two to eight hours, with an average of five hours. Again, these numbers are good news for anglers, suggesting that billfish are capable of a relatively rapid recovery in recreational fisheries, and that catch-and-release practices can be an effective approach to conserve and sustain billfish populations. It is important to note that all of the fish in the study remained in the water during tagging and were released as quickly as possible. Removing any billfish from the water is not recommended because it has been shown to drastically increase stress levels and mortality probability.

Hopefully this gives you an appreciation for what a marlin or sailfish goes through after you release it, and you can feel good about knowing that the fish you release will most likely recover and live to fight another day. To learn more about this study, please visit etps.ghriresearch.org.