Most fishermen have heard of El Niño: a climate event where trade winds weaken and the equatorial warm-water band that occurs when the jet stream moves southeast into the central and east-central Pacific Ocean, specifically around the equator, is pushed eastward, toward the west coast. La Niña, however, is the counterpart of El Niño, and has opposite effect. Here, the trade winds blow harder than normal, pushing this warm-water pool westward, promoting cold-ocean upwellings to replace the departing warm water.

Collectively, El Niño and La Niña are part of a larger, natural climate fluctuation referred to as the El Niño Southern Oscillation. ENSO not only affects global weather patterns, but also economies, ecosystems, and gamefish such as tuna, sailfish, marlin, wahoo and dorado found specifically in California, Mexico and Central America. Drastic changes in water temperature in these regions of the eastern Pacific Ocean can certainly affect fish distribution, migration patterns, survival, reproduction and behavior.

Watch: We show you how to rig one of the best baits for blue marlin: the swimming mackerel.

Two Phases

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, we are currently in a La Niña phase that should stay well into spring and is similar to this past winter’s pattern. These phases are more pronounced in the winter months, and La Niña tends to have the opposite effect of the El Niño phase. The La Niña phase in the ocean is caused by and associated with stronger trade winds in the equatorial Pacific Ocean. Winds push warmer waters west, leaving lower-than-normal temperatures and a stronger upwelling in the eastern Pacific coastal regions. Cooler waters in the eastern Pacific displace the jet stream in the Northern Hemisphere more northward, leading to dry conditions in the south and southwestern United States and more precipitation in the Northwest region. Normally, this translates to fewer hurricanes during the warmer months in the eastern Pacific due to stronger wind shear, while it equates to additional hurricanes in the Atlantic Ocean due to weaker wind shear and less atmospheric stability. Therefore, the weather-window opportunities increase for offshore anglers in the eastern Pacific, and decrease the opportunities in the northern Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico regions.

Predicting the effects of ENSO events on fisheries can be difficult because no two El Niño or La Niña events are the same, varying greatly in intensity and duration. The development of each ENSO phase involves common processes however, resulting in some insight on the general oceanographic trends of La Niña and how it relates to gamefish distribution.

Fishing Changes

The ENSO originates along the equatorial region and therefore has to be quite strong to influence Mexican and Southern California fisheries. If you’ve been fishing the past few years off the SoCal coast, the warmer waters associated with El Niño and “the Blob” drew tropical and subtropical species farther north, presenting a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to catch species such as dolphin, wahoo and marlin in local waters that are typically found in more-southern and -western waters.

In contrast, the phase shift to La Niña will promote the westward and then southwestward-to-northwestward movement of the population of warm-water species such as yellowfin tuna to the western Pacific, contracting these species south and west in the eastern Pacific. In a sense, the recent phase shift to La Niña has returned Southern California and Baja species composition back to “normal,” with staples such as tuna and yellowtail available to target.

As La Niña affects the trade winds’ push of warm water, the upwellings pull cooler, nutrient-rich water up through the water column to replace the westward movement of the warmer water. With this upwelling, the nutrient-rich water now riding on the surface in the eastern tropical Pacific creates an idyllic food chain. There has been plenty of research showing La Niña phases associated with strong and sustained upwelling events leading to plenty of primary production.

So, what does all this mean for us anglers? It means a higher concentration of sardines, anchovies and squid along coastal zones where the upwelling occurs and the promotion of a healthier population overall, with more food available. These increased baitfish populations and distribution from north to south within the eastern Pacific coastal regions typically will bring in higher numbers of pelagics. Unless it is a very strong La Niña event, the sea-surface temperature of the upwelling a few miles from the coastal regions will remain in the preferred habitat range of most sought-after gamefish species in the coastal eastern Pacific.

Big-Game Exceptions

La Niña events in the eastern Pacific support more nutrients and marine life, and attract species that can tolerate—or prefer—cooler water such as squid, bluefin and bigeye tuna to such places from California to northern Mexico. But there is a fine line to consider: Too many nutrients along the coast could cause phytoplankton and algae blooms that suck oxygen from the surface water, driving fish farther offshore, or deeper into the water column. Ocean color and chlorophyll data, as well as SST information, will give you an indication that should keep you from wasting your time fishing in the dirty green inshore waters.

La Niña events also tend to produce shallower thermoclines. Fish have a preferred temperature range, and thermoclines act as a physical barrier of sorts. With less room to roam within the water column, surface pelagic fisheries are thought to improve because your target species is more likely to be confined higher in the water column. However, this does not apply to all fish, especially the larger ones such as tunas and billfish because they can tolerate a broader temperature range, allowing them to comfortably dive through the thermocline to forage.

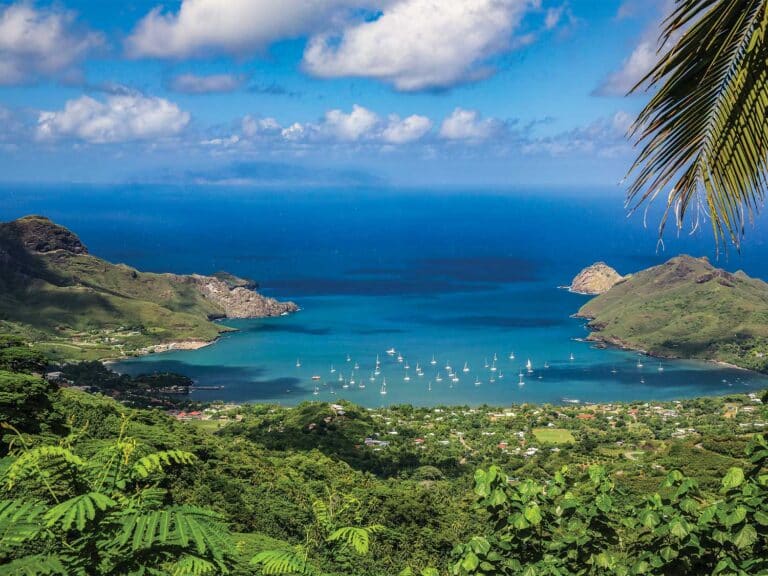

Read Next: An inside look at one of the sport’s most iconic destinations, Tropic Star Lodge.

Longtime recreational fisherman Capt. Dan Lewis on Sporty Game often fishes out of Cabo San Lucas, Mexico, and says he notices different trends in fishing for marlin with these varying ocean conditions. One observation that lines up well with the ENSO phases is that as the water gets too warm, the thermocline gets deeper, and many times, the baitfish and marlin resort to diving deeper into the water column, making it more difficult to find the larger fish. If the water is cooler, as in the typical La Niña years in the tropical eastern Pacific, and still within the preferred habitat range, marlin are slightly easier to “find,” giving you a better chance for a successful trip.

To learn more about La Niña and the effects of this phase of the current ENSO phenomenon, please visit

cpc.ncep.noaa.gov. This article originally appeared in the March 2022 issue of Marlin.