Special delivery: Sign up for the free Marlin email newsletter. Subscribe to Marlin magazine and get a year of highly collectible, keepsake editions – plus access to the digital edition and archives.

Being out on the water when the marlin start to chew can be a challenge in and of itself. But more times than not, it’s the reward for fishing every day. Some fisheries are more telltale than others, giving away the secret with the forecast of an approaching cold front. Or, sometimes you can see it coming with an abundance of surface activity, such as birds, tuna and flying fish on an edge. Other spots seem to give only subtle whispers, and Kona, Hawaii, is one of those mysterious locales. The clues are always there; however, it often takes a seasoned captain to pick up on them—and to be in the right place at the right time.

Unfortunately, the nature of the beast—or should I say beasts—is that you can never be 100 percent sure of when the bite will happen, especially when speaking about Pacific blue marlin. Oftentimes in Kona, the captains might call or email clients to inform them that they are seeing the signs of a bite about to explode off the coast and to get on a plane. Of course, that tactic can work us into hero status, or, by the time your clients have finished their first cocktail in the departure lounge, the bite has already shut down.

You Shoulda Been Here Yesterday

More common than not, a condition will change overnight, and the fish will be gone or never even show up. It is often said that when people ask about when to come to Kona, “when you can” is usually the answer because the nature of this place is that if the conditions line up, it can happen whenever. In terms of big fish, a lot of times, the truly large ones might make an appearance for a day or two, with no real indication. So, that is why, when these epic bites occur, it’s the holy grail of big-game fishing. If you are fortunate enough to be a part of it, especially as a traveling angler, you can consider yourself lucky and definitely in the minority.

This brings me to the focus of this piece, and one that revolves around a fantastic bite that occurred in Kona in January 2023, during our “offseason”—a bite of mythical nature the likes of which is hardly ever seen in Kona, besides one other time in recent history. It was an epic bite and was dubbed “Blue Monday.” It took place in the 1990s for only a couple of days, but this one that happened earlier this year was something that will go down in history as an anomaly, a legendary big-fish bonanza that will most likely never be rivaled. It is being called “Jurassic January” because it truly lasted about a week and a half before slowly tapering off.

Just to give you an idea of the numbers, longtime fisherman “Kaiwi Joe” Thrasher, who came to Kona in 1991 and is a crewman and photographer, kept accurate stats during this time, which show that in the first week, the fleet had 129 reported fish seen or hooked over 400 pounds, with at least half of them over 600 in the first seven days.

Keep in mind that we are talking about only a handful of boats because it truly was the offseason. Most captains were either out of town or doing boatwork. If this phenomenon had occurred in the summer months during our high season, then I’m not even sure what kind of numbers we would have seen. There was a lot of talk of some fish so big that conventional tackle and even the best skippers could not keep from breaking them off against the speed and water pressure of a giant blue on 130-pound-test.

Unfortunately for me, I completely—and painfully—missed it because I had just hauled out my 37-foot Merritt for a massive refurbishing project the day before this spectacular feeding frenzy began. From most accounts, Dan Holt on Sea Baby encountered the first pack. I was standing in dry dock taking off my outriggers when a friend of mine who was helping me had just received a text that Holt was 3-for-6 with a 500-, a 650- and a 700-pounder. I was immediately stoked for him, figuring he must have found a weird nest of big girls. We sometimes see numbers like that, but not often. I didn’t feel sick to my stomach until an hour later, when he told me they just released a 900-pounder and were headed back in, going 4-for-7 on all big fish. Those are near-unheard-of big-girl numbers for Kona. I know Holt well enough to know that he did not overestimate the size of those fish and that his report would have been accurate.

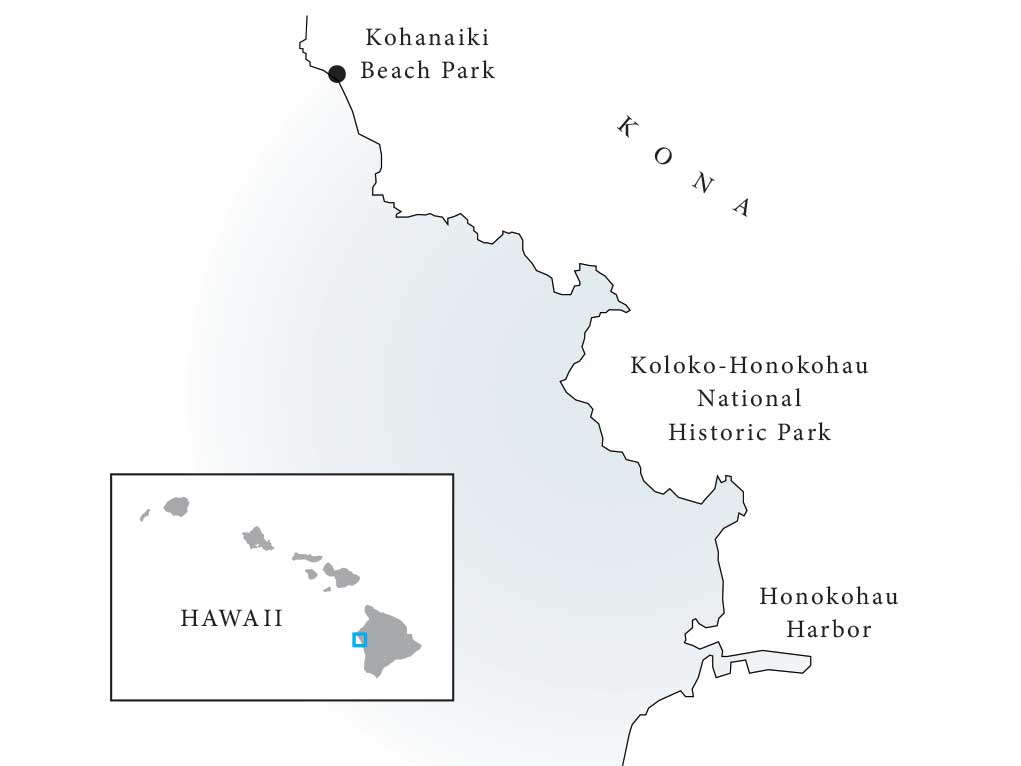

From that point forward, the reports poured in, and here I was fixing the rotted wood on an old Merritt boat while the most historic bite was occurring just off the coast. When I say just off the coast, I am not exaggerating. The frenzy’s epicenter was straight out from the Honokohau Harbor and up to Kohanaiki Beach Park, an area we call the Pine Trees, 7 miles north. Talk about a spectator sport—you probably could’ve driven up to Kaloko and sat around with binoculars watching as the boats roared around in reverse to chase down those big girls just off the beach.

Although I was missing out, I was still extremely fascinated by the details of this unprecedented offseason bite and promised myself that I would explore the factors that may have contributed to it. I wanted to learn as much as I could in the hopes that I’d be prepared for it—if, God willing, it ever happens again.

Fire Up the Technology, Theories and Ideas

With all of the technology available to us these days, predicting good fishing can be a lot easier than in years past. Things such as satellite sea-surface charts, image-mapping services, and the advancement of fish-finding technology, including the controversial but extremely effective omnidirectional sonars, sometimes finding a bite is a lot more scientific than instinctual. This technology allows us to paint a picture of what could have happened—or didn’t happen—for a bite of these proportions to unfold, seemingly out of the blue in Kona.

I spoke with Capt. Kevin Hibbard of 2nd Offense, who has been fishing in Kona since 1995. He is a legendary big-fish captain in his own right and was a top boat during this phenomenon. He fished just three days during this historic event, missing a 500-pounder, catching two 600s and a 700, and pulling the hook on an 800-plus-pound monster. Hibbard has become quite savvy in the operation of his omni sonar, and when I asked him if he was chasing individual fish or just looking for big ones, he remarked that there were so many big ones on the sonar that it was hard to even pick one at all, saying that it was better to just fish along and try each target as you went, with no need to circle back if she didn’t raise.

Hibbard had a few theories that he thinks could explain why the big girls were there. One was the cooler water temperatures, which could keep the smaller, less-cold-tolerant males away, and the larger and more-tolerant females around. The other was the clouds of bait that made your sounder look as if it were broken and you were marking the bottom (which is impossible). He later determined that these clouds of bait were made up of ultra-tiny red shrimp, among other things, confirming this by examining the stomach contents of the tuna caught by the fleet. The presence of these shrimp would also explain the abundance of whale sharks in the area. A correlation was also made that the marlin caught were abnormally fat, and seemingly growing fatter by the day.

I also was able to catch up with another Kona legend, Northern Lights’ Capt. Kevin Nakamaru. He has fished all over the world and pioneered some big-fish spots alongside the best of the best, and certainly knows a thing or two about marlin bites. He too believed that this occurrence was attributed to all the bait. “The bite that we experienced was amazing. It was nothing like anything we have ever seen. Four to five boats would be hooked up to nice fish at the same time, and the luckier boats caught two big ones in a day. It was similar to bites I have seen in Ghana and Madeira, and the same vibe to get out there was in the air, and for two weeks, the fishing was awesome,” he says.

While no one can prove that it was the biomass of shrimp, plankton, sardines and marlin-candy-size tuna that contributed to all the activity, we do know that when the shrimp disappeared, so did the marlin. Nakamaru says that as the bait moved north, so did the fleet, and even as the bait dwindled, the big tuna and marlin stuck around, and they were able to capitalize on it. He even was able to fill the fish box with nice ahi before the bite shut down. “We know that in Kona, in any given month of the year, we could have this happen, but when it does, it’s nice to be a part of such a rare event,” he says.

Thrasher also chimed in with a few interesting facts of his own. He agreed with the others that the sardines, tuna and all the bait around contributed to this historic event. However, he did observe an interesting feature about those fish: It seemed that they were full. They were not at all feeding like a super-hungry marlin, but more so just as a reactionary predator would—almost as if they were biting the lures for sport or for the thrill of the chase. As those feeding patterns persisted, it generally resulted in some pretty crazy bites but not the best hookups. I assume that these fish must have been gorging themselves on all the bait but just couldn’t turn down a good lure when it came into their territory.

To dive deeper, I spoke to my buddy Capt. Kenton Geer, who runs the commercial tuna boat Vicious Cycle out of Kona, to get his take on things. Funnily enough, in contrast to the epic fishing we were seeing inshore, Geer told me that the fishing out on the seamounts was awful. He didn’t see any marlin at all during these weeks, compared with how it usually can be. So, whatever was going on with this bite off Kona, it seemed to have been concentrated inshore—a localized phenomenon, if you will.

Geer and I have been talking for a while about the correlation between the big blue marlin evacuation from the seamounts and the big-fish bite inshore. He was telling me that he’s noticed for many years that whenever the big blues are stacked up and harassing his tunas and then suddenly disappear, that a bit later on, you can expect a few days of everyone inshore seeing some monsters. Of course, I’m not aware of any conclusive scientific research to back up this theory, but I am aware of the fact that commercial fishermen are likely the closest to nature, and that whenever Geer says anything about anything, I pay attention, especially if the right moon phase is just around the corner.

Surprisingly, there weren’t any other theories floating around, particularly those around spawning behavior—mainly, I surmise, because of the little talk around smaller fish, and that the fish seen were only of the nicer size class. It could be possible that the small males were being pushed out of the area by the lower water temps, or that they just hadn’t arrived with the bait. Either way, I’m banking on the fact that the excessive amount of bait triggered this bite. The question now becomes: What brought all this bait inshore, and what, if anything, held it there long enough for an unheard-of marlin bite to develop because of it?

The Conditions

Satellite-mapping services continue to bring more information into the fold when it comes to understanding weather and the oceanic conditions associated with it. Several companies use all of the elements available to them to put together a bite prediction in certain areas. One company that I have used a lot in my fishing endeavors is ROFFS. So, naturally, I called ROFFS president Matt Upton and spoke with his team, who just recently added Kona to their service list of fishing-forecasting analysis areas.

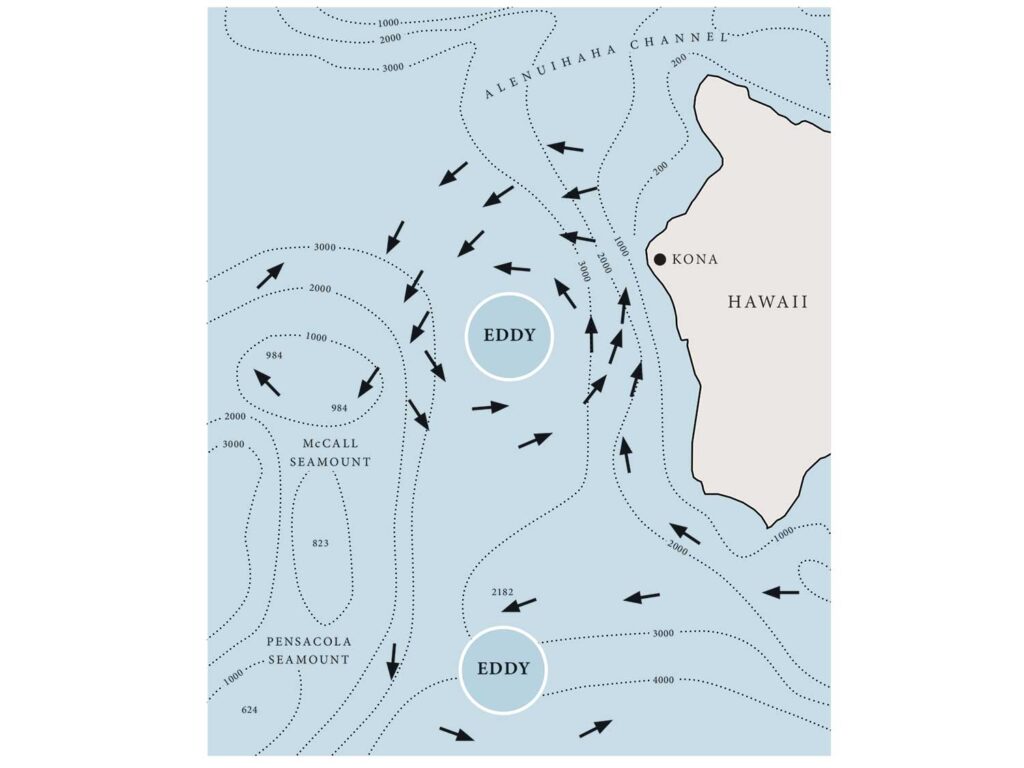

ROFFS has been instrumental in finding good bites all over the globe by monitoring the ocean conditions via satellite, especially off the Atlantic coast, so I knew that I was in good hands and was anxious to hear the team’s theories and ideas on this epic happening. Looking back at old charts, they started to do some detective work. Upton concluded that “the normal counterclockwise rotating eddy closer to the Hawaii coastline was pushing water in a favorable inshore direction. This land-destined eddy can produce upwellings, where nutrients so close to the Kona coast start the life cycle: phytoplankton, zooplankton, etc., then finally, baitfish, bigger fish—the ones that marlin feed on.”

Additionally, the larger winter rain events produced increased runoff that also spiked algae and phytoplankton blooms, which could also contribute to the increase of productive waters close to shore and enhance the food chain, bringing in the blue marlin. The water temps appeared to be between 74 and 75 to 76 degrees. I’m not sure if that is above or below normal, but in my experience, it is well within the temperature range that blue marlin prefer. The aforementioned eddy also pushed up—and in—some darker blue, but slightly warmer, water from the south. And water pushing in a deeper-to-shallower direction over the ledges always makes for good conditions around the coast.

So, we can build a hypothesis using the elements that created such a phenomenon, but it seems that there are still some variables that cannot fully be explained. The only thing we can be certain about is that a bite like the one that happened this winter in Kona is something we might never see again, but as Kona goes, it could also happen again in a week, a month, or even a year. Even still, the key to being part of a bite that is off the chain is simply time over target, local knowledge, using the conditions to your benefit whenever possible, taking full advantage of the available technology, and understanding the weather and satellite charts and images, as well as the accounts and reports you get from other captains.

A captain can have all the technology at his fingertips and all the sonar video games at the helm, but it’s still hard-earned learning experiences and knowing how to effectively use that information that makes for a banner day on the water. A great marlin captain never relies on just one piece of the puzzle; he uses all of the information available to him to formulate his inference for when and where to catch fish. A good marlin captain just gets by.