A vast, productive portion of the Pacific Ocean abounds off the coast of Panama. Known as the eastern tropical Pacific, nutrient-rich currents there associated with the northern flank of the Humboldt Current converge with slow-moving equatorial currents to create extremely prolific ocean conditions that promote the aggregation of apex pelagic predators including billfishes, tunas and sharks. In fact, some of the largest aggregations of marine life in our oceans, including hammerhead sharks, manta rays and black marlin, occur in the vicinity of Panama and within the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean. Another amazing species that thrives in these waters is dolphinfish, one of the world’s most highly esteemed fish on our planet for both sport and food.

Dolphin occur annually off the coast of Panama, but beyond that, virtually nothing is known about the species’ local and regional movements, habitat use, seasonality, and other region-specific life-history traits such as age and growth patterns, diet, and reproduction. Also lacking are additional data on commercial landings and catch per unit effort, despite the estimate that Panama and nearby countries including Ecuador, Peru, and Costa Rica provide the majority of global dolphin production, estimated at 47 to 70 percent from 2001 through 2012. It is also estimated that in some locations such as Ecuador, dolphin are thought to constitute the vast majority of estimated landings of pelagic fish, a situation that is likely true for other countries in the area, including Panama.

Given these estimates and the lack of fundamental data, there is an urgent need to gather information on dolphin in order to improve the management and conservation of this critically important species in the region.

Watch: A belly-strip teaser is a great way to raise marlin and sailfish.

Dolphin Tagging Successes

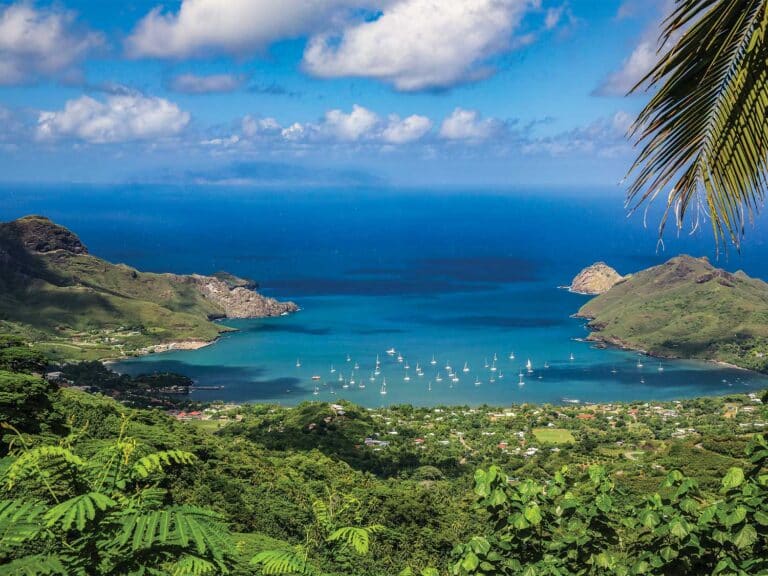

Since 2018—with the support of Dr. Guy Harvey, the Guy Harvey Ocean Foundation, Guy Harvey Research Institute at Nova Southeastern University, and Tropic Star Lodge in Piñas Bay, Panama—the Dolphinfish Research Program has helped 154 anglers begin to tag and release dolphin during the annual Tropic Star Lodge Marlin Tournament. This ongoing effort is beginning to describe their life-history traits, movements and population dynamics in the southern portion of the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean.

Throughout the history of the DRP, dedicated anglers have traveled with tagging kits to places such as Baja California, Guatemala and Costa Rica, and have tagged a few fish, but never with the quantity and consistency necessary to produce meaningful results in the eastern tropical Pacific. One goal of the DRP has always been to expand the program throughout the Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Sea, where it has been hugely successful. Since 2002, more than 30,892 dolphin have been tagged and released by over 5,600 anglers and 1,720 participating vessels. This effort has produced 755 recaptures and 42 satellite-tag deployments. These results have led to eight scientific manuscripts on topics such as movements, diving behavior, population structure and oceanographic preferences, which have helped management agencies implement and improve conservation measures that benefit the health of dolphin that occur in the western central Atlantic. Now DRP’s goal is to replicate its efforts in the Atlantic and Caribbean with efforts in the eastern tropical Pacific, based out of Tropic Star, and beginning at Casa Vieja Lodge in Guatemala in January 2023.

Moving to the Pacific

As of spring 2022, a total of 572 dolphinfish ranging in size from 15 to 52.5 inches have been tagged and released in 79 trips out of Tropic Star Lodge. The average fish size tagged was 31.3 inches, which is much larger than fish tagged and released along the US East Coast by DRP participants, which average 20.2 inches. While it is likely that the larger fish size tagged is related to the size of bait the fleet uses in Panama, as well as the presence of a minimum size along the US East Coast, there were also very small individuals tagged, which is evidence to support that all size classes for the species are present simultaneously off Panama, suggesting that stock and recruitment dynamics for the species might be adequate to support a consistently healthy population. In addition, preliminary conventional tag movement data suggests that small fish—less than 5 pounds—can recur off Panama over a year later, after growing 10 to 15 pounds, but it is still unknown where those fish moved during their time at large.

Other conventional tags have shown movements to the high seas outside the exclusive economic zone off Costa Rica in 96 days, as well as other locations along coastal Costa Rica and Panama in 17 to 40 days. All those tags were reported by commercial-fishing activity with the high-seas recovery reported from a Venezuelan-flagged purse seiner, showing that dolphin are a shared resource between recreational and commercial sectors.

To fill in movement knowledge gaps, satellite tags are being deployed to acquire additional information such as vertical diving behavior and geolocation tracks of tagged fish to further determine regional and seasonal movements. During the past three annual expeditions to Tropic Star, our team has deployed 20 satellite tags on adult female and male dolphin ranging in size from 36 to 56 inches. This effort has led to 132 days of vertical diving behavior that shows vertical movement activity is generally shallower—less than 200 feet—than vertical movement activity in the Atlantic and Caribbean regions. These observations are consistent with the vertical activity of other pelagic predators such as blue and black marlin and sailfish due to lack of dissolved oxygen at depth in this region of the Pacific. This condition is described as habitat compression and has been documented several times by researchers. Geolocation estimates—approximate locations for where a tagged fish moved while at large—can help to answer part of this question, especially as it relates to which sectors and countries are currently targeting dolphin, and on what spatial and temporal scales do individual fish, schools, and population biomass overlap.

Read Next: Learn more about the Dolphinfish Research Project here.

The beauty of this effort to gather more data on dolphin in the eastern tropical Pacific is that any offshore angler can get involved. Free tagging kits are being shipped to anglers throughout the region as well as distributed at major tournaments and events. To get involved, visit dolphintagging.com to request a kit and read more about the preliminary results the project is beginning to collect.

A special thanks goes out to the entire staff, captains and mates at Tropic Star for their assistance in making this endeavor possible as we help to restore and conserve Panama’s precious ocean resources for generations to come.