Special delivery: Sign up for the free Marlin email newsletter. Subscribe to Marlin magazine and get a year of highly collectible, keepsake editions – plus access to the digital edition and archives.

For most anglers who venture to Guatemala’s Casa Vieja Lodge, dorado is not likely the target species. The superior power and size of blue and black marlin, striped marlin, and sailfish—combined with high encounter rates—make those species the goal. For me, however, dorado is the research subject—not because I don’t enjoy catching marlin and sails, but because dorado is one of the most poorly understood and documented fish species in our oceans, especially off the coast of Guatemala.

In a recent search of dorado landings associated with the Food and Agricultural Organization’s global landings database, which is the global source for quantifying annual landings of virtually any finfish or shellfish species, the government of Guatemala recorded only 1 metric ton of dorado landings in 2019. In fact, of all the nations with commercially harvested dorado in the Eastern Tropical Pacific Ocean, Guatemala ranks last. Yet, artisanal pelagic longline activity is high and might rival adjacent efforts off El Salvador or Nicaragua.

Accuracy is Key

Surely one would imagine that this fishery would amount to orders of magnitude greater than 1 metric ton of annual commercial landings. Why does this matter? If you like to eat dorado when you travel to the eastern Pacific, or if you live anywhere throughout the region and want to continue to rely on dorado as a food source, it is important to make strides toward improving our ability to document and understand this iconic gamefish. Without accurate landings, movement, and growth data, enabling a sustainable dorado fishery in the region will be impossible.

Fortunately, Casa Vieja supports enabling a sustainable dorado fishery, and recently—with funding provided by the Guy Harvey Foundation and sponsors of the Dolphinfish Research Program, a globally recognized international tagging program for dolphinfish—Casa Vieja’s anglers began to tag and release small dorado to aid in data collection on this species throughout the region. DRP’s recent expedition to Casa Vieja early in 2023 adds to an ongoing effort that began in 2018 at Tropic Star Lodge in Panama to describe the species’ life-history traits, movements, and population dynamics in the eastern Pacific through hands-on angler and citizen participation. These actions, while small locally, are impactful regionally, and are a big step toward enabling a sustainable dorado fishery in the future.

Tagging-Expedition Success

In three days of fishing with Casa Vieja’s Capt. Sammy Baires at the helm of Release, and with the assistance of Chris Whitley and mates Sergio Alvarado and Tony Martinez, our team was able to execute six flawless deployments of pop-up satellite archival transmitters on dorado ranging in size from a 39- to 43-inch fork length.

These are the first satellite-tag deployments on the species in Guatemalan waters. Spindrift and Makaira also participated in the tag-and-release of 20 more dorado with conventional dart tags. In total, 26 fish were marked in three days of fishing, which signified an excellent start, and the effort has already produced meaningful results.

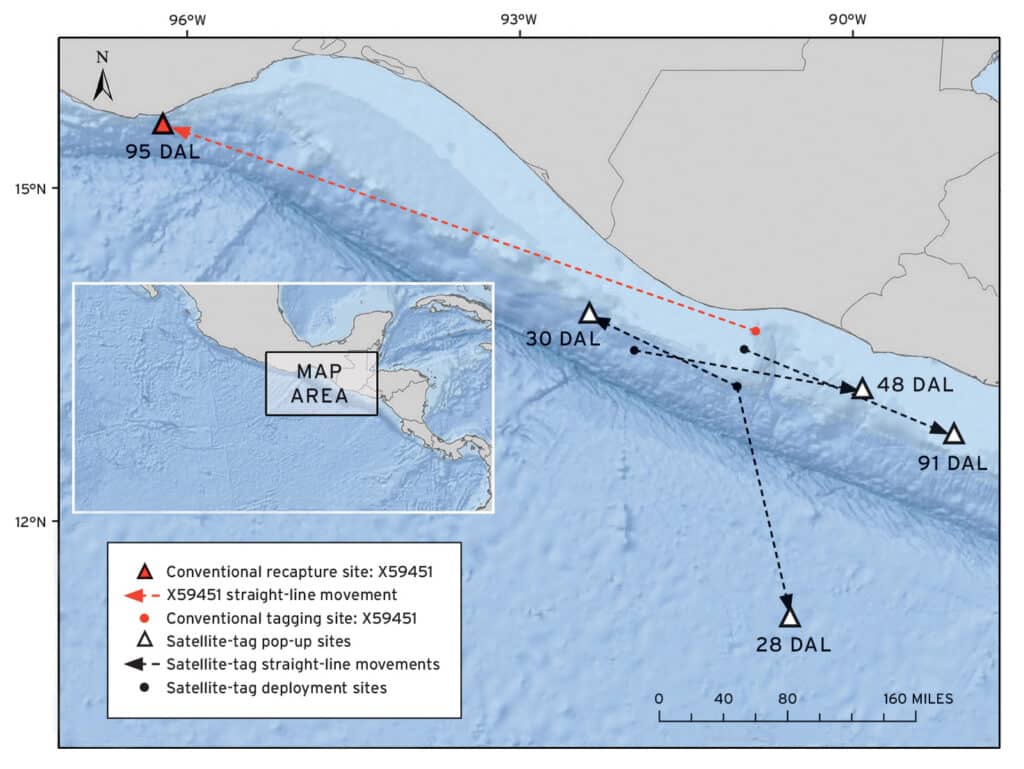

Two of the 26 fish were recaptured, equating to a 7.6 percent recapture rate. A 39.5-inch female carried one of the PSATs for 28 days to a location 150 miles southeast of the tagging site off El Salvador, and a 42-inch male that was tagged at the same site moved 100 miles to the west-northwest and carried the tag for the full 30-day monitoring period. The maximum depth obtained during this bull’s monitoring period was 293 feet. Two additional satellite tags were carried for 48 days, and another for a 90-day monitoring period. Both of these bulls moved east-southeast with tags surfacing near the continental shelf, similar to the bull that moved to the north. Lastly, the second conventional recovery depicted a movement of 95 days to the west-northwest, where the fish was recaptured off Oaxaca, Mexico.

These results not only dispute the presumption that individual dorado will remain in Guatemalan waters, but they also show that the species is connected between nearshore and offshore fisheries, among nearby nations, and appear to use the continental shelf edge as a corridor for movement to the northwest and southeast.

Dorado Data Collection in the Eastern Tropical Pacific

Coupled with our recent efforts in Guatemala and the ongoing research in Panama, a total of 977 dolphinfish, ranging in size from 15 to 59 inches, have been tagged and released in the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean. Of the 39 recaptures, the average fish size was 34 inches, with the majority of the recoveries submitted by small-scale artisanal anglers based in Ecuador, Panama, Costa Rica, Mexico and, now, Guatemala.

Preliminary conventional-tag movement data suggests that small fish (less than 5 pounds) can recur off Panama more than a year later after growing to 10 to 15 pounds. It is still unknown, however, where those fish moved during their time at large. Other conventional tags have shown movements to the high seas outside the Exclusive Economic Zone off Costa Rica in 96 days, as well as from the high seas to coastal Costa Rica in 141 days. To fill in movement knowledge gaps, satellite tags are being deployed to acquire additional information such as vertical-diving behavior and geolocation tracks of tagged fish to further determine regional and seasonal movements.

In total, 26 dorado have been released with PSATs. One geolocating satellite tag carried by a 44-inch bull traveled more than 1,600 miles in a nearshore-to-offshore movement south of Panama and west of the coast of Colombia. The daily average movement rate was 36 miles per day, and daily rates ranged from three to 98 days throughout the 45-day monitoring period. The track shows an actual path and evidence that large fish can recirculate off Panama and Colombia within short time frames. When combined with conventional tagging data, this supports the notion that all reproductive-age classes of dorado can engage in regenerative spawning activity off this part of the Pacific. In addition, the track showed that the bull engaged in routine nighttime deep-diving behavior throughout the six-week monitoring period, which could support an effort to reduce deep-set commercial-longline activity at night to avoid bycatch of dorado during yellowfin tuna fishing activities.

Read Next: Get to know Casa Vieja’s owner, Capt. David Salazar, in our exclusive interview.

In partnership with Casa Vieja Lodge, the behavior and movements of this species can now be determined from a distinct location in the Pacific. This partnership also allows comparing and contrasting geolocation estimates as well as vertical-movement patterns. In total, our satellite tagging effort has led to 396 days of vertical-diving behavior mainly from off Panama, with the potential of 120 days added from our recent work off Guatemala. What remains to be determined is how horizontal and vertical movements and habitat use might vary between the northern and southern Pacific, as well as how this compares to other ocean basins such as the western central Atlantic Ocean, where our program has been collecting data on dorado since 2002.

With this recent effort, free tagging kits are being distributed to anglers, tournaments and other events throughout the Central America region. To request a kit and to learn more about the results the DRP is acquiring from our efforts in Guatemala and Panama, please visit dolphintagging.com/etp.