Special delivery: Sign up for the free Marlin email newsletter. Subscribe to Marlin magazine and get a year of highly collectible, keepsake editions – plus access to the digital edition and archives.

Blue marlin are a cosmopolitan and globally distributed species, and are often the focus of offshore anglers’ dreams. However, new research utilizing electronic tags is showing that this migratory predator’s habitat might be shifting, and where you target these fish in the future may shift as well.

Over the years, tagging studies using both satellite and conventional methods have taught us that oceanic predators such as billfish and tuna are capable of extensive migrations that span ocean basins, international boundaries, and tens of thousands of miles. From these studies, we know some basic biological and ecological information about billfish, but the physical drivers of their movements are still relatively unknown.

Fish Response

All billfish migrate to find optimal waters for spawning and feeding, as most fish do, but we know very little about their spawning requirements. In order to better conserve and manage all billfish species, we have more work to do.

Blue marlin are known as epipelagic fish, meaning they live predominantly at the sunlit zone that exists from the surface to a depth of 200 meters. Here, they are top predators with only occasional dives into the deeper twilight zone. They play a critical role in maintaining the health and function of the open-ocean ecosystem, therefore characterizing their distribution and habitat use is vital for effective fisheries management. This is especially true as the oceans change on a global scale. How fish respond to such environmental changes likely varies from one species to another, so understanding the habitat preferences of different fish species, and the factors that shape those preferences, provides a more informed understanding of the management and conservation actions necessary to ensure a healthy population in the face of Earth’s changing climate.

A New Study

An eye-opening new study explored blue marlin habitat preferences and documented how the distribution of preferred habitat is shifting due to changing ocean conditions. The study was conducted by International Game Fish Association Great Marlin Race (IGMR) collaborators from Stanford University’s Hopkins Marine Station, including lead author Dr. Jonathan Dale. The research team analyzed an extraordinary dataset of 144 blue marlin tracks, many of which were collected by the IGMR’s tagging efforts as well as the earlier efforts at the Hawaiian International Billfish Tournament.

This study took a complex statistical approach to estimate the habitat preferences of blue marlin across three ocean basins—the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian—by comparing tracked positions generated by an algorithmic methodology based on tag sensor data of tagged fish to local environmental conditions. Imagine following hundreds of blue marlin as they swim across the globe, then creating a list of all the ocean conditions they experienced over these long migrations. The study found the most important environmental factors to include sea-surface temperature, sea-surface height, dissolved oxygen concentration, ocean depth, and chlorophyll concentration.

Once the statistical model revealed those most important factors in determining where blue marlin spend their time, researchers were able to map these conditions across the entire globe. We know from previous studies that implement IGMR data that blue marlin are impacted by their environment. It’s been found that billfish behavior is not only influenced by local environmental conditions, but also by ocean-scale cycles such as El Niño/La Niña oscillations that impact temperatures and thermocline depths, resulting in distribution shifts in the Pacific. A previous article published by the Block Lab also found that La Niña conditions limited blue marlin migration southward across the equator in the Pacific Ocean.

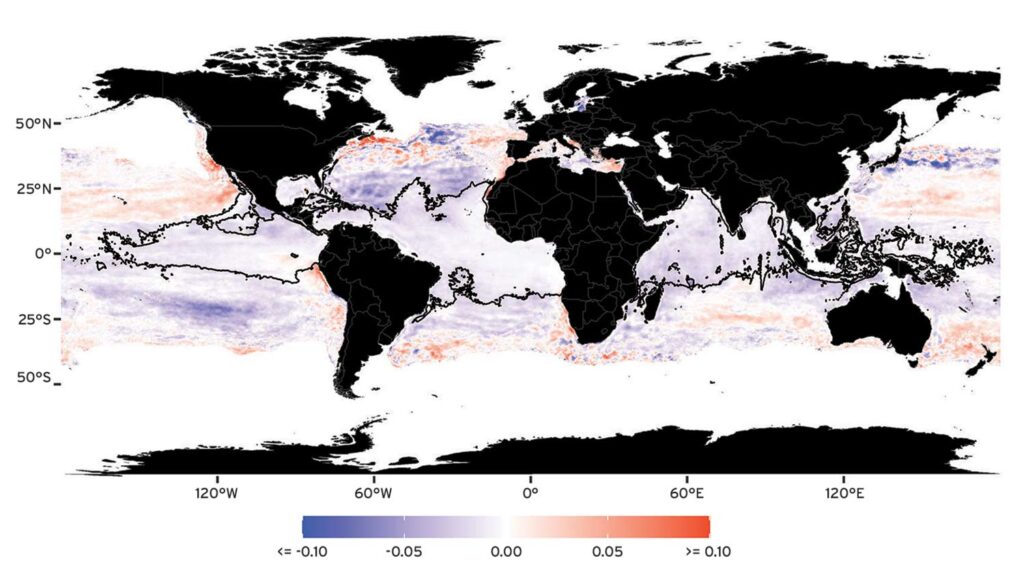

Knowing that blue marlin are affected by their physical environments (e.g. temperature, low-oxygen levels), the research team, working together with their National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration collaborators, built a database of habitat-preference conditions and examined how these variables affect blue marlin seasonally, as well as over a 16-year timeline. Results from the analyses show that the most suitable habitat ranged from 40 degrees N latitude to 30 degrees S, which was to be expected because this is the range where blue marlin are currently caught and targeted by anglers. Suitable habitat was found to be broadest north to south in the Atlantic, and spanned farther north than in the Pacific.

The eastern Pacific, along the west coast of North America, showed the broadest north-to-south extent of suitable habitat. Suitable habitat was also found on the western side of the Hawaiian Islands, but the western Pacific had smaller—and patchier—suitable habitat. The majority of the Indian Ocean was deemed suitable for blue marlin, but overall, the core habitat for blue marlin was typically distributed around the equator. Unfortunately, the researchers found that blue marlin habitat had a positive relationship with the global commercial-longline-catch index over the course of the study, suggesting that these fish might be vulnerable to extensive fishing pressure.

Perhaps the most important finding of the study was that suitable habitat as a whole is decreasing over time. The researchers estimated that 96 percent of the core blue marlin habitat experienced declines over the 16-year span of the study. Declines were found to be highest in the North Atlantic, the Indian Ocean, and the South Pacific regions east of French Polynesia and Japan.

Although the future outlook of blue marlin preferred habitat is changing, with equatorial waters becoming less suitable, all is not lost. The study also found that suitable habitat is increasing in some regions, occurring at the north and south edges of blue marlin range in the Atlantic and Pacific, especially in the North Pacific and Northwest Atlantic.

More Questions

The results of this study bring about some important questions: Because blue marlin core habitat surrounds the equator and they are known to regularly cross this region, will blue marlin migration patterns shift as equatorial waters continue to warm and hold less oxygen? Might we one day see genetically different blue marlin populations in the Northern and Southern hemispheres? And how likely are we to see fisheries target blue marlin in higher latitudes?

Only time and more research will tell. This type of study is critical to understanding how our blue marlin fisheries are going to change with time, and this particular study showed that a citizen-science-based research program such as the IGFA Great Marlin Race can be successfully used in conservation and management as changing oceans force this species to adapt.

Read Next: How long does it take a billfish to fully recover after release? The answers might surprise you.

The IGFA Great Marlin Race

Partnering with Dr. Barbara Block’s lab at Stanford University, the IGFA Great Marlin Race is a satellite-tracking program and is the largest billfish-tracking database collected by citizen scientists. Recreational anglers fund and deploy these tags to learn more about the behavior of billfish across the globe.

As of December 2022, the IGMR has deployed over 500 satellite tags on seven of the nine species of billfish in 22 countries around the world. These tags have resulted in more than 35,000 days of tracking information and enough tracked mileage to circle the globe more than 15 times.

One of the most important aspects that differentiates the IGFA Great Marlin Race from other research programs is that the data is made fully available to any scientist or organization working to learn more about billfish, and to date, the program has facilitated 11 peer-reviewed scientific publications. To preview this data, please visit gtopp.org.