Special delivery: Sign up for the free Marlin email newsletter. Subscribe to Marlin magazine and get a year of highly collectible, keepsake editions – plus access to the digital edition and archives.

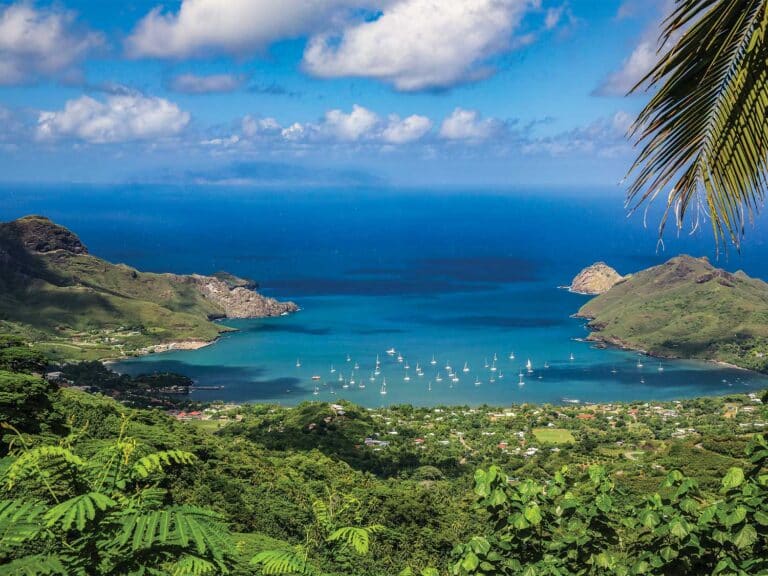

As I look out the window of the single-engine prop plane, an unbelievable sight unfolds: to my right, a vast ocean sprinkled with turquoise reefs and atolls as far as the eye can see; to my left, a dry, rugged wilderness stretching across the landscape to the horizon. After a nearly 30-hour journey from San Francisco, it’s a welcome view as I’ve finally arrived at perhaps the most famous black marlin destination in the world—Australia’s Great Barrier Reef.

As the plane banks left on final approach, I see a muddy river that empties into the ocean at the small seaside community of Cooktown. After the plane touches down, I am greeted not just by the blanketing warmth of the tropical air, but also by a sense of awe and respect for the untamed wilderness that now surrounds me. While waiting for a ride to town, I see a sign by the river that puts the remote wild into perspective: “Beware of Crocodiles.”

My excitement is palpable as I’m transported back in time to my first trip to the reef in 2018 when I fished for 10 days with Capt. Brett Goetze and experienced some truly unbelievable fishing. Over 12 days, we released 26 marlin, including two that were over 950 pounds. After that trip, I have been itching to return, not only for the amazing fishing, but also to better understand what makes this place so special. I want to learn more about the biology, migration patterns, and behaviors of the black marlin that frequent the reef for a few short months each year.

Big Boats and Big Fish

After a short taxi ride, I head toward the Cooktown Wharf, where I’m meeting Goetze and get my first look at Akira, a completely remodeled 78-foot Warren that was formerly the famed Little Audrey. As the wharf comes into view, I’m immediately taken aback by myriad beautiful gameboats tied up there. I walk up to Akira, and Goetze and I exchange greetings after a long three-year hiatus.

“Welcome back! Get ready for an awesome few weeks,” he says as I am introduced to Elliot Muller and Jimmy Reddon, Goetze’s two mates for the 2022 season. Wasting no time, we head to a local bar to get acquainted over a few Great Northern beers. After our first round, I realize that Muller is something of a legend on the reef. He has fished 17 straight seasons here, weighing multiple blacks over 1,000 pounds, including one of the largest marlin in recent memory: a 1,431-pound monster in 2018. By contrast, this is Reddon’s first season on the reef, and I can tell that he is trying to soak in as much information as possible.

Early the next day, we meet our first charter, and soon we’re heading to Ribbon Reef No. 6. As we approach the reef, Goetze slows the boat and calls down from the tower: “Bait rods!” Fishing on the Great Barrier Reef is unique—not only do you fish for giant blacks, but it’s also critical to catch fresh bait for the afternoon of fishing. After a mere five minutes, the center rod goes off. Following a short battle, a 15-pound mackerel comes over the side—the perfect bait for a huge marlin. Over the course of a few hours, we catch a variety of species, including mackerel, tuna and scad, and are well-prepared for the afternoon’s marlin fishing.

“Let’s head to the edge,” Goetze says from his perch high above. Muller rigs the Penn International 130s and deploys the standard reef spread: On the left is a big skipbait—the mackerel from earlier in the day—on the shotgun is a 10-pound tuna, and on the right is a swimming 2-pound scad. All set.

After a few hours with little action, Muller is in the middle of telling us about his giant marlin, saying, “It was an unbelievable fish, and so many things could have gone wrong—ON THE LEFT!” We all stare at the big mackerel skipping on the surface, and I squint as my untrained eyes are trying to determine if I see a shadow under the bait. As I was trying to block the sun from my eyes, the water erupts—a black marlin has inhaled the bait. The circle hook finds its mark, and the line starts ripping from the reel as the fish greyhounds across the surface. The client scrambles into the chair, and Goetze begins backing down on the fish, with water pouring over the transom. After a grueling 20-minute battle, Muller grabs the leader, and the marlin goes ballistic jumping behind the boat. Eventually, he gets the marlin under control, and the 450-pounder is calmly swimming next to the boat. After a few pictures, Muller releases the fish, and with a flick of the tail and a wave of water splashing into the cockpit, the black returns to the depths.

The Mysteries of the Marlin

At our comfortable anchorage behind the reef, we celebrate the day’s catch over a few beers and some seared yellowfin tuna. As the sun begins to set, I look out at the breaking waves on the outer reef and think, What makes this such a special place for these fish?

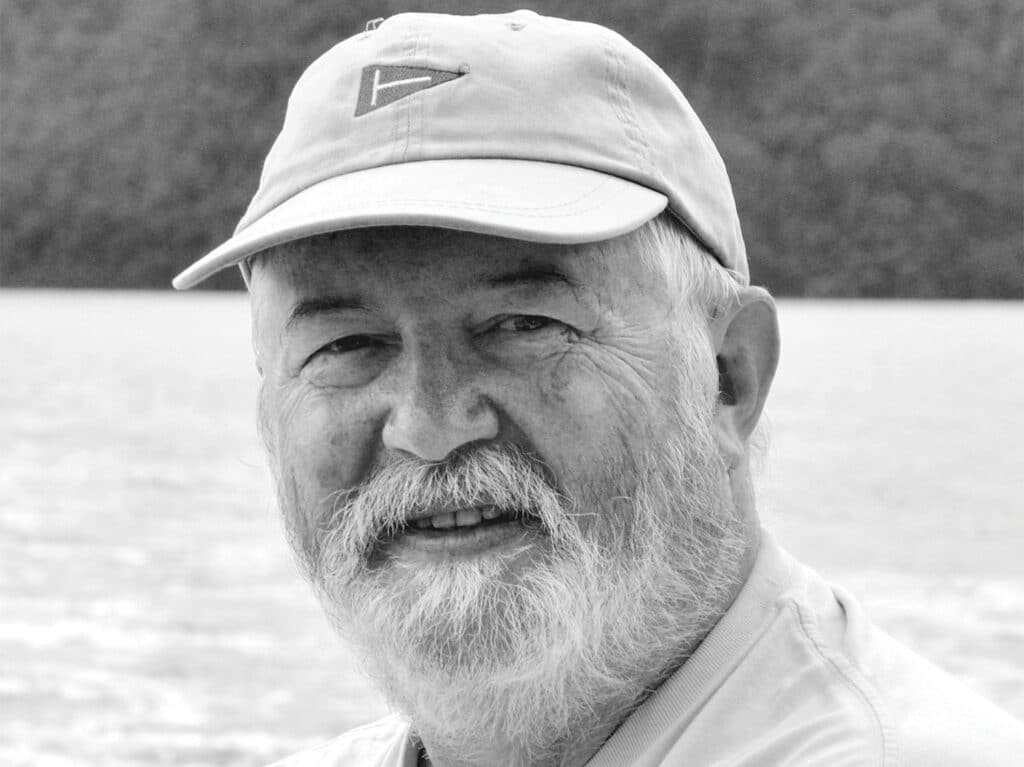

To help answer this question and to learn more about this species, I enlist the help of Dr. Julian Pepperell, a marine biologist who specializes in black marlin. During our discussion, it is apparent that while modern science has made significant breakthroughs, just as many mysteries remain.

The history of recreational fishing for black marlin on the reef dates back to the early 1960s, when biologists began to study Japanese longline reports from the 1940s and ’50s. These reports showed an astonishing number of huge fish being caught here from September through November. After seeing these reports, an American named George Bransford set out on a quest in this untapped fishery. After losing many big fish and carefully fine-tuning his techniques, Bransford finally caught the first grander black marlin of 1,064 pounds in 1966. With this catch, the scientific community started to take notice, along with recreational anglers from around the world.

Pepperell tells me that aggregations of black marlin largely occur for two reasons: to spawn or to feed. On the beaches of Lizard Island in the 1970s and ’80s, biologists dissected large female blacks, and Pepperell and other biologists soon realized that the marlin had come here to spawn. “When looking at these large females, we realized they had mature eggs,” he says. “In some of the large females we examined, we found that they can carry up to 200 million eggs each. Moreover, there is a run of small black marlin down the east coast of Australia every year, and this is a direct result of the spawns happening on the northern Great Barrier Reef.”

When I ask about other spawning locations, Pepperell smiles. “Until about 10 or 15 years ago, we weren’t sure if the Great Barrier Reef was the sole spawning ground for black marlin,” he says. “However, with the recent advancements of genetic testing, we’ve found that there are at least three proven spawning aggregations: the Great Barrier Reef, one off Taiwan, and one in the eastern Indian Ocean, likely off Indonesia.” As a fisherman, this is intriguing because I hadn’t heard about recreational fisheries for blacks in either of these other locations. Pepperell says: “To my knowledge, I don’t believe that recreational fishermen often fish the other two spawning aggregations. It just makes you daydream about the possibilities for someone with the resources and time to figure it out.”

While we know that these fish come to the reef to spawn, I ask where they spend the majority of their lives. “We still have a long way to go, but the IGFA Great Marlin Race in 2014 was extremely interesting,” Pepperell says. “Partnering with the recreational fleet, we were able to deploy 23 satellite tags, including some on large females over 700 pounds. Initially, we believed that these larger females stayed within the vicinity of the Coral Sea near the Great Barrier Reef. However, this was thrown completely out the window. A handful of large females traveled over 3,500 miles away from the reef, with one fish estimated at 1,100 pounds traveling an astonishing 5,716 miles directly toward Peru and the famed Cabo Blanco fishery of the 1950s.”

This immediately piques my interest because I’ve spent countless hours looking at the old black-and-white pictures of huge blacks that were caught off Peru. After seeing my expression, Pepperell continues: “Cabo Blanco was likely a feeding aggregation, as almost all the catches were between April and August, well outside the spawning season on the reef. Also, when looking at the Cabo Blanco fishing club records, only 5 percent of the blacks recorded were under 400 pounds. On the other hand, around 70 percent of fish caught on the reef are under the 400-pound mark, which are the smaller males.”

Chasing Shadows

The next day, we head to the famed Ribbon Reef No. 10, one of the largest outer reefs spanning over 50 miles. On the back side of the reef, we deploy bait rods to prepare for the afternoon of marlin fishing. After trolling for 30 minutes, the left side erupts as a large fish inhales the Nomad swimming plug. After a screaming run, Goetze yells down, “Marlin!” To everyone’s surprise, a 100-pound black starts jumping behind the boat. After a tough battle on light gear, we are able to release our first marlin of the day. “You just never know what you’ll catch out here; the reef is full of surprises,” Muller tells me with a grin. Over the next few hours, we experience some unbelievable fishing, catching more than a dozen scaly mackerel, two jobfish, and numerous small tuna.

Around 1 p.m., we venture to the outside of No. 10 and set the marlin baits. This time we don’t have to wait long. “Shotgun! Shotgun!” Goetze yells from the tower, as we all pivot and see a massive black shadow beneath the skipping 12-pound tuna. Suddenly, a marlin’s huge bill slices out of the water behind the tuna, and an explosion of water soon follows. We hold our breaths as the drop-back comes tight. Instead of a massive run, the marlin stays in place and starts shaking its massive head from side to side. After what seems like an eternity, the marlin comes alive and strips over 100 yards of line with 30 pounds of drag over the course of a few seconds. Then, like a missile, it launches itself out of the water and lands with a loud smack. However, as soon as the marlin hits the surface, the line goes slack. No one on the boat says a word, bewildered and stunned at what we just experienced. We are all thinking the same thing: Just how big was that enormous marlin?

The Afternoon Hunt

Unlike most marlin fisheries, fishing for blacks on the reef usually occurs in the afternoons from around 1 p.m. until sunset. When I ask Pepperell about this seemingly odd behavior, he explains: “In the early days, most captains would marlin fish from sunup to sundown, but it soon became apparent that the vast majority of bites occur in the afternoon. As scientists, this was something we wanted to further understand.”

So, Pepperell and his team conducted an experiment to deploy acoustic tags on marlin and follow them over the course of 48 hours. “We found that the marlin we tracked tended to stay close to the surface at night, but around dawn, they would dive to the thermocline, around 60 to 100 meters. Then around midday, they would ascend to the surface much more often,” he says. “Around dusk and into the first few hours of the evening, the marlin would be extremely active, zigzagging near the surface. We don’t have a lot of data on why this occurs, but one hypothesis is that they feed on squid in deep water during the day, and then on pelagic fish near the surface. But we just don’t know for sure.”

The Enigmatic Predator of the Pacific

Over the course of the next 10 days of fishing on Akira, we release 17 marlin, with a handful over 500 pounds. However, looking back on the trip, I’ll never forget seeing that huge marlin inhale the tuna and slam into the water on that fateful final jump. The Great Barrier Reef is truly unlike any fishery in the world, from the fun of baitfishing and spearfishing during the day to fishing for huge marlin in the afternoon to anchoring behind the reef at night, reminiscing about the day’s action over drinks and dinner. While there have been significant scientific advancements in understanding these magnificent creatures, these studies have also uncovered countless more mysteries where even more research is needed.

Near the end of our meeting, I ask Pepperell what excites him most about the future of black marlin research. “There’s just so much we don’t know, and the opportunities are endless,” he says. “But a few areas come to mind, including a better understanding of the black marlin population in the western Indian Ocean near Mozambique, where little research has been done; reevaluating the Cabo Blanco populations, given recent satellite-tagging tracks; and, perhaps most of all, continued investment in genetic testing to uncover untouched spawning populations, which, I believe, are out there.”

For any serious marlin fisherman, the Great Barrier Reef is a truly special place. While I’ll be back soon, I’m also itching to explore other parts of the Pacific to perhaps play a small part in gaining a better understanding of this mysterious species.

Read Next: Here’s another look at the fishery out of Cairns from a different perspective.

The IGFA Great Marlin Race

A partnership between the International Game Fish Association and Stanford University, the IGFA Great Marlin Race pairs recreational anglers with cutting-edge science to learn more about the basic biology of marlin and how they utilize the open-ocean habitat. The goal of the program is to deploy 50 pop-up satellite archival tags in marlin at billfish tournaments around the world each year, which will help increase understanding of the distribution, population structure, and biology of marlin, while also engaging anglers and the general public in the research process.

The concept behind the IGMR is simple: Billfish-tournament teams are invited to sponsor PSATs to be placed on the fish they catch and release. Then, 240 days after each tag is deployed, it automatically pops off the fish and transmits information to Earth-orbiting ARGOS satellites, such as where the fish traveled, its diving behavior, and the water temperature it inhabited. The tag that surfaces farthest from where it was deployed wins the race for that particular tournament. The overall winner of the IGFA Great Marlin Race—the team whose tagged marlin traveled the greatest distance in a given year—is recognized by the IGFA.

Tag sponsors, anglers, and the general public are able to view the migration routes of tagged marlin through satellite-enabled maps on the IGFA website displaying marlin tracks and pop-up tag locations. This open-source information can also be used to enact better international conservation measures for marlin around the world.