“Ladies and gentlemen, welcome to Kona. The local time is 2:30 in the afternoon. Enjoy your stay in Hawaii.”

With that announcement, the flight attendants cracked open the forward- and rear-entry doors, flooding the aircraft with the warm floral scent of plumeria mixed with a hint of saltiness carried on the ever-present trade winds. As I made my way down the stairs and across the tarmac to the open-air terminal—old school, no jet bridges here—I couldn’t help but smile in the bright sun. Welcome, indeed.

I’d come to Kona with several different goals in mind. Because it was my first trip here, I wanted to check out what is undoubtedly one of the most historic blue marlin fisheries anywhere in the world. This is where it all started, going back to Capt. George Parker’s first blue over 1,000 pounds, landed back in 1954. The IGFA All-Tackle Record is also from Kona: Jay de Beaubien’s 1,376-pound beast from 1982. It’s the birthplace of modern-day lure-fishing. If you’re a blue marlin fisherman, this is hallowed ground.

Watch: Learn to rig a swimming mackerel here.

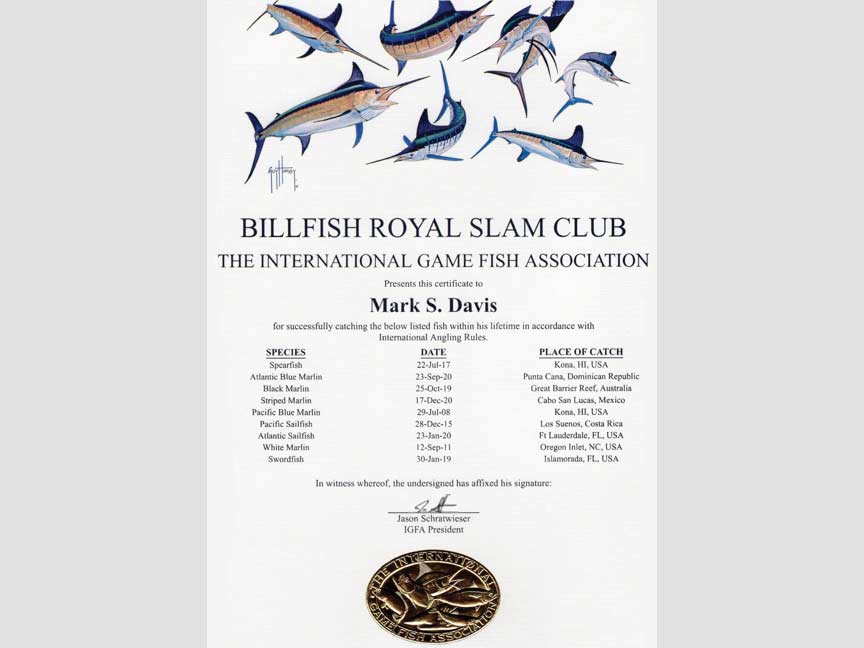

But I had also ventured to Kona in search of the most diminutive and little-understood of the world’s billfish species: the spearfish. For anglers seeking the IGFA Billfish Royal Slam Club, catching a spearfish is almost always the hardest part of the equation. To date, there have been just 199 verified Billfish Royal Slams caught by 160 different anglers; incredibly, Mark Davis has accomplished this feat 18 times in his career. In addition, four anglers have done this on fly, and Roy Chronacher Jr. has slammed out an amazing four times with the long rod.

The IGFA’s Slam Club programs began in 1995 under then-IGFA president Mike Leech, with the launch of the Offshore and Inshore Grand Slam clubs, which require the capture of three species of fish within a given day. With the early success of those programs, the organization expanded with the addition of Royal Slam clubs in summer 2001. At the top of the list is the IGFA Billfish Royal Slam Club: Atlantic blue marlin, Pacific blue marlin, black marlin, striped marlin, white marlin, Atlantic sailfish, Pacific sailfish and any species of spearfish.

What Do We Know?

In order to learn more about this elusive species, I reached out to two top scientists for their input: Dr. Julian Pepperell and Dr. Freddy Arocha. “Even though spearfish are true billfishes in every way, they are often neglected or ignored by science and anglers alike,” Pepperell says. “Even so, our knowledge about them has gradually increased, at least to the extent that we now know how many species actually exist.”

He points out that while spearfish share many of the same characteristics of their sailfish and marlin cousins, there is one notable area in which they are different, and that’s the location of the vent. “In all spearfishes, this opening is located well forward of the base of the anal fin—at least as far forward of the anal fin as the longest spine of that fin—whereas in the other billfishes, the vent is located just forward of the base of the anal fin,” he says.

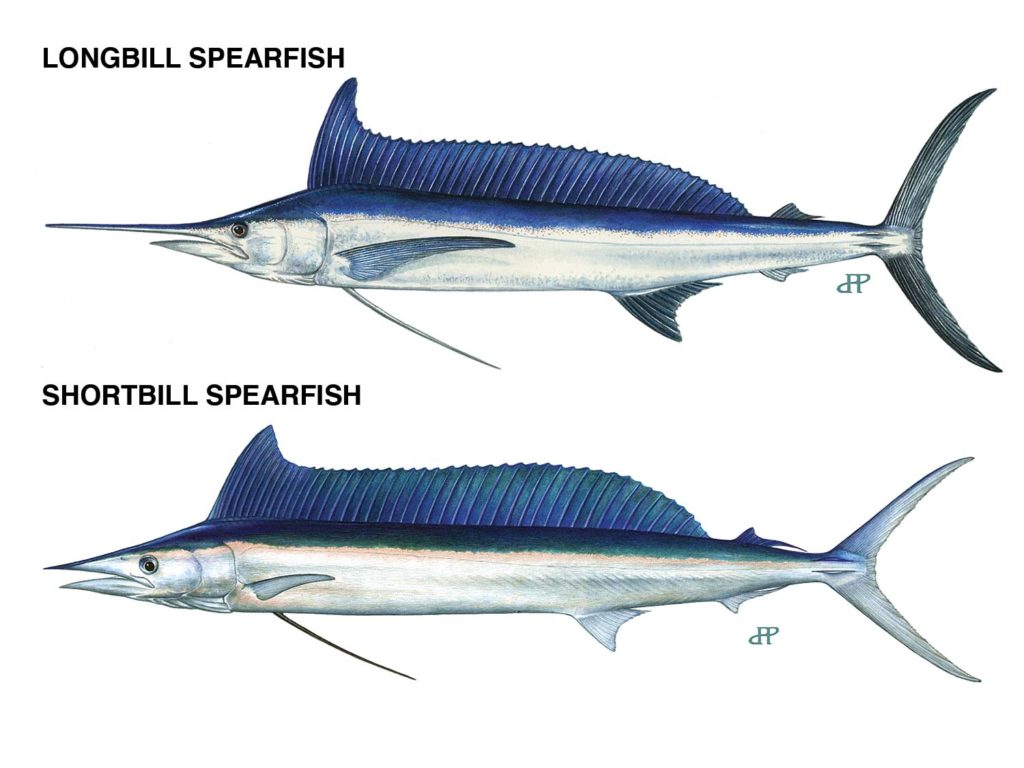

He says that there are four distinct species of spearfish around the world. “The shortbill spearfish is the only spearfish that occurs throughout the Pacific and Indian oceans,” Pepperell says. “In the Atlantic and Mediterranean, however, three species of spearfish are found: the longbill spearfish, the Mediterranean spearfish and the now-confirmed roundscale spearfish, which was originally recorded only in the Mediterranean and off Portugal but more recently in the western Atlantic.”

Commercial fishermen started seeing some unusual billfish being caught off Venezuela in the late 1980s, so a formal scientific program was begun there in 1991 through ICCAT, using a combination of in-port sampling of commercial landings as well as at-sea observers on commercial boats. As the use of cameras became more commonplace, researchers such as Arocha, from the Oceanographic Institute of Venezuela, noticed that there were increasingly more landings of a billfish species that looked like a small white marlin but with the vent much farther forward. Soon, landings were recorded not only off South America’s northern and eastern coasts, but throughout the western Caribbean as well. The longbill was legit.

Hawaii’s the Place

I asked a few well-traveled captain friends about their spearfish encounters, and the answers were typical of what I’d learned from my research: They’re found in a lot of different areas, but unless you get really lucky and stumble across one, spearfish encounters are pretty rare. It seems that the longbills show up off North Carolina’s Outer Banks sporadically for a few weeks in late summer, and they’re also caught throughout the Bahamas from time to time, but they can appear in the spread just about anywhere along the mid-Atlantic region. The same goes for shortbills in the Pacific—generally speaking, they can be caught from Cabo to Costa Rica but with maddening infrequency. It’s just impossible to target them with any semblance of certainty, with one exception: Kona.

Capt. Chris Donato has been fishing here for the past seven years on his 37-foot Merritt, Benchmark. Prior to relocating to Honokohau Small Boat Harbor, he helped develop a surf camp and a corresponding fishery for blue marlin and giant yellowfin tuna in Western Samoa, catching his grander blue there along the way. I wanted to tap into his knowledge and experience for a spearfish trip, starting with his thoughts on the peak season.

“As far as the best times of the year, I think that spring is best, but it’s hard to pinpoint one month,” he says. “I do feel that in April and May there are definitely a bunch here pretty much every year, but they’ll show up in waves and disappear just as quickly. We catch them all through the summer, but spring is the best time to target them.” Hedging my bets and rolling the dice, I booked three days with him during the first week of May and crossed my fingers.

For anyone who’s never experienced the fishing out of Kona, there are a few immediate impressions, and they’re all pretty cool. First, it gets deep here—quick. The thousand-fathom curve is right at the sea buoy, so most charters don’t even run before laying out the riggers and setting the spread. The water is the most gorgeous shade of blue-purple that you can imagine, and it’s nearly always flat-calm because you’re fishing in the protected 30-mile lee provided by the mountains of the Big Island.

Heavy tackle is the rule. Big blue marlin are caught here year-round but especially in spring and summer; they have a way of finding the lightest outfit you have, so the locals don’t tempt fate. These are also some of the best lure-fishermen on the planet. Donato will do bait-and-switch fishing for any client who wants to give it a shot, but for me, it wasn’t worth the hassle of bringing my own gear all the way from Florida.

“What I won’t do is pull light line classes that time of year,” he says. “I’ll be happy to tease-and-switch, but I don’t like hooked lures out there on light tackle in the spring. There are just too many giant once-in-a-lifetime marlin that can show up, and they will eat a tiny bullet when you least expect it. Having a 1,200-pound fish eat a 20 or 30 would be devastating.”

When my wife and I arrive at the boat, we are pleasantly surprised to find Capt. Chip Van Mols working the cockpit. He is between boats and is filling in for a few trips early in the season until Donato’s full-time mate arrives from the mainland. Having lived in Hawaii since the 1980s, Van Mols is a wealth of information about not only the fishery, but the history and island lifestyle too.

Setting the Spread: Colors and Styles

Donato and Van Mols both agree that jets and bullets are among the very best lure styles for spearfish, which are called “chuckers” locally. “Even if we’re fishing for spears, I like pulling a marlin lure on the short corner,” Donato says. “I think it excites them into the pattern. I like the XL Bandit from Tantrum in blue-and-pink on that short corner. On the long corner behind a pink squid dredge is a pink Tantrum AMN or Aloha Deep Six bullet.” For the short rigger, he likes the Tantrum Jetpack in blue Flashabou over white-and-pink, while the long rigger gets a Tantrum medium bullet in blue-and-white with white wings—a dead ringer for a flying fish. On the center stinger is a Koya 9-inch bullet in purple, white and yellow flash. “All of these lures are rigged with 9/0 Tantrum hooks except the bigger lures, which are 10/0s, and everything is on 530-pound-test Momoi X-Hard leader in case a big blue piles on.

“Sometimes the spearfish get switched on to pink or red, possibly because they’re eating a lot of squid, so we might lean toward those colors if I hear any of my friends are having their ‘pinky’ piled on,” Donato continues. “I sometimes like a red or brown flash color on a bullet early in the morning too, thinking that maybe the squids are still around then. And if we are seeing a lot of little bait in the water, I might even go with a green bullet. The main thing is that I like to have a good spread of bullets out there—some jetted, some not, some with more taper and a little bit different action. I definitely want one bullet doing a lot of dish-ragging, while another one does more of a black-water ripple, and a third one with more of a pop, ripple and a slight skitter. It takes a lot of adjusting through the day to keep them doing this correctly,” he adds.

Read Next: Everyone needs a few good knives for fishing. Here are our top choices.

Donato fishes his lines using a Dacron hanger loop in the outrigger clip and with tag lines to reduce the amount of drop-back on the bite. Periodically throughout the day, Van Mols adjusts the hanger loop up and down the main line, sometimes in increments as small as a foot or less, in order to keep the lures performing at their best. He also points out that with two bullets in a five-lure spread, that style accounts for well over half of his blue marlin bites—that’s 40 percent of the lures producing 60 percent or more of the action. Based on those numbers, I’ll be pulling a lot more jets and bullets at home in the eastern Gulf of Mexico this summer.

On the Water

As Benchmark settles into an easy trolling mode, the allure of fishing in this idyllic destination quickly sets in as we simmer in anticipation. Around midmorning on the first day, a bite on the stinger lure has everyone’s spirits up, especially when a second spearfish comes greyhounding in after the long rigger lure as it was being cleared. In the flurry of excitement, a small blue marlin swipes at a bullet on the short rigger, but unfortunately none of the hooks stay connected, and just like that, we are 0-for-3. Day Two, another spearfish knockdown and no hookup, but we do release an acrobatic 150-pound blue marlin for my wife, her first. On the third and final day, with just 15 minutes left to fish, I am finally able to wrangle a spearfish within range of Van Mols’ outstretched gloves. Moments later, we release the chucker in good shape amid high fives all around. From the bridge, Donato remarks that the old Merritt still has a few ghosts left in her, and I completely agree. Kona might keep you waiting, but she never disappoints.

The Billfish Royal Slam

According to Zachary Bellapigna, the IGFA’s angler recognition coordinator, in order to qualify for the Billfish Royal Slam Club, an angler must catch each of the following species over the course of their lifetime: Atlantic sailfish, Pacific sailfish, Atlantic blue marlin, Pacific blue marlin, black marlin, striped marlin, white marlin, swordfish and any species of spearfish (the IGFA holds line-class records only for Atlantic and shortbill spearfish, but they do maintain all-tackle records for all species of spearfish, including Mediterranean and roundscale).

Fish do not need to be harvested to qualify; photos of the angler and fish and/or contact information of witnesses to the catches are required as part of the application process, and IGFA angling rules must be followed.

“Members of the IGFA Billfish Royal Slam Club are recognized as some of the most dedicated and accomplished billfish anglers on the planet, and each member is listed in the annual IGFA World Record Game Fishes book and on the IGFA’s website,” Bellapigna says. “Members of the club also receive a custom, hand-signed certificate featuring artwork from IGFA Hall of Famer Guy Harvey.” To learn more, visit igfa.org.

Getting There, Staying There

For continental US-based anglers (or from anywhere else for that matter), it’s a long haul to the Hawaiian Islands. Based on your departure destination, you might need to fly into Honolulu on the island of Oahu, then over to Ellison Onizuka Kona International Airport at Keahole. We were fortunate to have a direct flight to Kona from Florida by way of Denver, but it’s a long one: four hours on the first leg and seven hours on the second. The good news is that because you’re flying west, many flights arrive in the midafternoon. The town of Kailua-Kona is a short 15-minute drive down the coast, along which you’ll pass Honokohau Small Boat Harbor on your right—this is where the majority of the island’s charter fleet is docked.

There are two popular options for visiting anglers: the historic Kona Inn and the King Kamehameha’s Kona Beach Hotel, the latter of which is a Courtyard by Marriott. Both are chock-full of angling history; the entrance to the Papa Kona restaurant is home to the famous Grander Wall, with photos of most of the 1,000-plus-pound marlin caught off Kona since George Parker’s first one in the 1950s. In the King Kam there’s a reproduction of the IGFA men’s 50-pound-test world record, which weighed 1,166 pounds, as well as many of the trophies and photos from the Hawaiian Invitational Billfish Tournament, the island’s longest-running fishing event. There are many other hotels in the area, as well as vacation rental homes and other options.

A note about transportation: At press time in early June, rental cars throughout the Hawaiian Islands were hard to come by, so if you are planning to travel, be sure to reserve a car as soon as possible.

This article was originally published in the August/September issue of Marlin.