I hadn’t seen my friend Capt. Anthony Mendillo in what seemed like forever. We met at the Viking Service Center many years ago, and when he invited me to spend a week with him and his wife, Kin, in Isla Mujeres, Mexico, I agreed I would — someday. The years passed, but when he extended another invitation, I jumped at the chance.

I had never been to Isla before, though I had always wanted to go. Visions of 30-fish days, amazing guacamole and the ancient Mayan culture were on my brain; after all, who doesn’t love tacos? So this time, without a single hesitation, I booked a ticket: nonstop, Miami to Cancun.

On Island Time

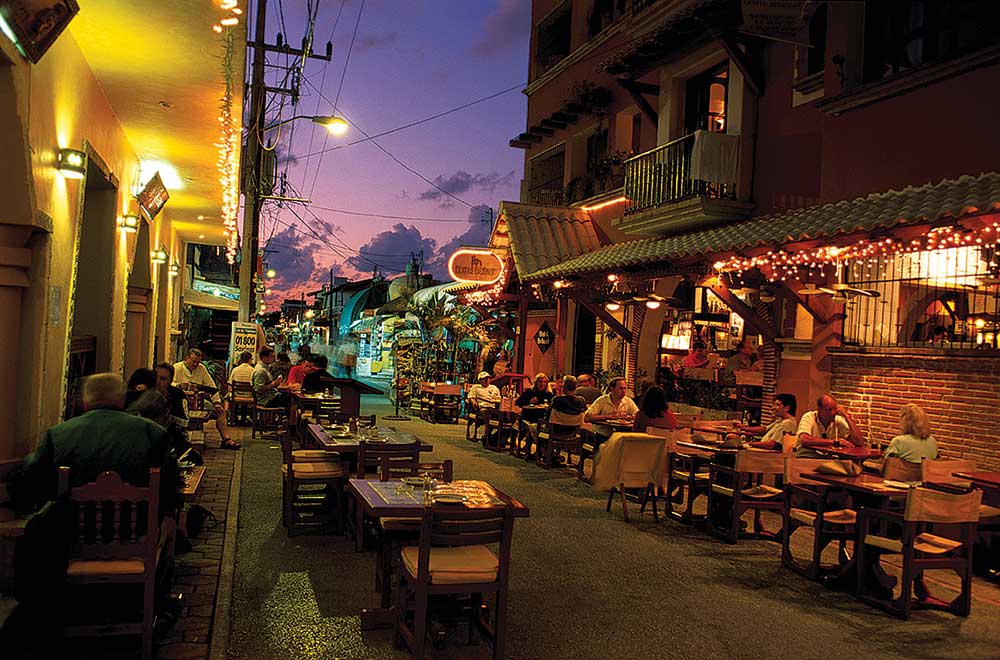

Stepping off the Ultra Mar ferry onto the island’s main drag — Avenida Rueda Medina — it seemed reminiscent of what you might consider the hustle and bustle of any other colorful tourist destination in the Caribbean: hordes of people, honking horns and scooters weaving in and out of the two-lane traffic like motorcycles on Florida’s Turnpike, a far cry from the Isla that Mendillo and many other fishing greats remember from the 1980s, when it morphed from just a sandy rock into one of the world’s premier light-tackle sailfish destinations, among other things.

I turned left and began walking north, suitcase in tow, along a sidewalk littered with people from all walks of life. I was on a mission to get to Enrique’s Marina, where Mendillo’s boats were moored — and on an even bigger mission to plop down with my first ice-cold Dos Equis.

Enrique’s was somewhat hidden behind a small gas station, but with the best of my Miami Spanglish I managed to get directions. Finally, I was there. After Mendillo returned from his charter, we sat down for a few cold ones and some dinner. It was only then that I began to unravel the story of Isla Mujeres and its odd but duly-needed rules — all implemented years ago by Mendillo’s father-in-law, Enrique Lima — eventually making the connection that it was here, in the late 1980s, that light-tackle, on-the-hunt billfishing techniques began to take hold, eventually creeping up the East Coast of the United States.

Viva Venezuela

Light-tackle fishing was not foreign to anyone fishing Venezuela in the early 1980s. North Carolina fishermen were exposed to it in small doses when the Ocean City Light Tackle Club would show up at the Oregon Inlet Fishing Center with their own tackle, ready to take advantage of the late-summer bite. In the eyes of the old-timers, it was laughable. They didn’t like it, and the term “catch” was very different than it is now. A catch was when your fish was splayed on the deck — taking a boat ride to the tournament scale or taxidermist. The charter fleet couldn’t think of any reason to stray from their big guns loaded with 80-pound-test mono and a good length of No. 15 wire when you were after blue marlin, or No. 7 wire for sails. After all, it is called wiring a billfish.

As word of the Venezuelan fishery got out, more American boats headed south after the St. Thomas blue marlin season, where the fuel was ridiculously cheap, grand slams were the norm and they could see for themselves just how well you could catch billfish on tackle normally reserved for schoolie dolphin or blackfin tuna. And it wasn’t long before the boats began scaling down their tackle and making stops in the Yucatan to catch the full-moon bite in Mexico.

Word Gets Around

For the American boats, Puerto Aventuras — simply called PA — and Cozumel were on the hit list long before Isla Mujeres. Tarheel‘s Capt. John Bayliss put in his time in PA when the sailfish showed up, but Isla Mujeres remained a well-kept secret for the handful of Texas and Florida boats that made the trip from the United States, primarily for the spring sailfish and late-spring white marlin seasons.Capt. Arch Bracher was one of the first North Carolinians to visit Isla when he was working as a mate on Catch 22 in 1988. He also accompanied Capt. Chip Shafer to Cancun for his first trip on Temptress with his then-mate, Capt. Mike Brady, in March 1990.

“We’d typically show up in April and stay well into May,” he says. “The sails would always bite on the full moon at the end of the month.

“Mexico was a decent bet to catch a grand slam, if you could get a blue marlin,” Bracher says. The blue marlin was the most difficult to find, but he points out, “If you could catch your blue in the morning, you already knew you were going to catch a sail in the afternoon, and in May and June, a white marlin was almost a shoe-in.”

Because of this opportunity and its proximity to the United States, it was the place to be.

The theory is that Mexico’s sailfish migrate from the Gulf of Mexico. As the strong northerly winter winds push them down through the Yucatan Channel between Cancun and the southwest tip of Cuba, they eventually find solace in the lee of the peninsula when the northwest-bound North Equatorial Current flowing through the Windward Passage guides them toward the sardines in the deeper water, pushing the bait up into the shallows toward some prominent structure known as the Ridge.

“Our best bite was always in the late afternoon, inshore and in the shallow water, where the bait was,” Mendillo says. “Fishing was generally good the whole time, but it would really get rolling for that 10-day window around the full moon. If you could get on the bait before the full moon rose in the afternoon, it was a slam-dunk.” On days when the moon was not in your favor, everyone would give the Ridge the attention it deserved, pounding out the last hours of daylight and fishing until dark. The spring sailfishing in Isla continued to be status quo for the next 10 years.

A New Fishery Is Born

Since the 1970s, the same methods had been used to target Isla’s sails, but the seas are not for the faint of heart. When an area’s weather got its own moniker — Isla rough — you sometimes had to wait it out, but it was usually worth it. “The colder the winter, the better the fishing,” Mendillo says.

By 1996, his first charter boat, Keen M, was on location in Isla. “The first couple of winters were not that good, but I was sure the fish were somewhere, just not in range for us with the weather we had,” Mendillo recalls. “There were some good days here and there, but nothing like what was about to come.”

After a hard, north blow in mid-January 1998, Keen M finally got off the dock. “I called my buddy, local charter captain Orland Duran, and he was flipping out,” Mendillo remembers. “He said I needed to be out there, like now, and yelled out the lat and long numbers on the radio, but I thought he had them mixed up.

“Duran was sitting just 4 miles from the break in 60 feet of water. When I got home that night, it all seemed like a dream. We had never seen that kind of action, and I called everyone I knew,” with Bracher and Shafer at the top of the list. The body of fish had been located, and Keen M managed to catch more than 1,000 sailfish that season.

The Arrival

Though the first American boats showed up in Isla in the late 1970s and early 1980s, Shafer and Bracher began to pay more attention to Isla in the mid-1990s, when an American captain — who was there to help show the area’s commercial boats how to fish in a more sophisticated manner — reported seeing sailfish jumping in the winter, well north of the typical sailfish grounds and the Ridge.

“After that, it wasn’t long before we started to go in January, and if it stayed good, we’d be there through May,” Bracher says.

As the American fleet began to hear rumors of double-digit days in Isla, the entire fishery began to make a turn. And why not? Especially when the normal double-digit sailfish day could easily turn into a 30- to 50-fish day with the right conditions. Subaru‘s Capt. Timmy Hyde made the initial move, and soon after, Bracher began bringing his own boat, Pelican. Bayliss, Sea Toy‘s Capt. Bull Tolson, Capt. Mike Merritt on Sea Pup, and Trophy Box — who were all in PA — followed, with many others coming after that.

Mendillo, who has been fishing the same grounds since the 1980s, says, “Our fishery changed dramatically when the North Carolina boats started coming earlier in the season, using their fast-trolling methods and small ballyhoo to cover ground.

“The Carolina-style fishing tactics changed the game, for the better,” he recollects. “I’ve been through two different fisheries in the same spot: old-school inshore, and roaming around at a faster clip. I learned from them how to find sails on the troll in my own backyard.

“Bracher is a student of the game,” Mendillo says. “He loves the sport and respected the history, but he and Shafer pretty much changed our fishery by expanding the horizons — both in season and tactics — in good ways.”

Instead of spending all morning at the dock, Shafer would venture out to get a head start on the rest of the fleet by fishing deep, even though the offshore bite could be anywhere from the usual 12 to an astonishing 50 miles north.

“While the other guys were battling the bonito in the shallow water, waiting for the sails to turn on, we would start offshore and work inshore as the body of fish did,” Bracher says. “After a while, we ended up staying through the winter and backing off our spring visit. By April or May, we’d be home getting ready for our own billfish season in North Carolina.”

Texans and Tequila

As the history of the fishery began to come together for me, Mendillo, an advocate and influencer of the island’s current sport fishing and conservation efforts, is following in his father-in-law’s footsteps. He says the island’s tourism and successful fishery is no accident.

Texas oil tycoon and founding chairman of the Gulf Coast Conservation Association (now the Coastal Conservation Association), Walter Fondren III, was introduced to Lima through Cuervo tequila producer Guillermo Freytag, a mutual acquaintance. The two quickly became, and remained, lifelong friends until Fondren’s death in 2010. Lima’s father was the minister of tourism for Mexico, but he settled on Isla, so Lima’s roots had him politically tied, seeing the need to conserve the island and its natural resources.

Lima played an instrumental role in creating some of the first national parks and marine sanctuaries in Mexico from 1961 to 1973. Contoy Island, Garrafon and Manchones reefs all have his stamp. His adoration and vision for Isla was mirrored by Fondren’s aspirations for his own beloved U.S. Gulf Coast.

Ahead of their time, Fondren — with his U.S. connections and guidance from the IGFA, as well as help from fishing icons such as Stewart Campbell, Don Hunt, Steve Slone and the Rybovich family — and Lima’s conservation ideas were recorded in the book of sport-fishing history, because the future of Isla’s fisheries were worthy of protection. And so came the rules.

Read Next: Dress Up Your Dead Baits with These Techniques

Codes of Conduct

Even with all the potential in the world, Isla Mujeres was still in its infancy in 1990, unlike the new Marina Hacienda del Mar in Cancun, with its unlimited dockage for the boats that came for the International Light Tackle Tournament and then the Masters, with the first being conducted in Mexico in 1992.

In Cancun, everything was just a cab ride away, while spending a season in Isla was somewhat austere without the right contacts. To thrive in Isla, your stay at the family-owned and operated Lima dock was the only game in town, and making friends with Lima afforded you all the help you needed to make it through your Mexico season in one piece.

By the mid-1990s, Enrique’s Marina was operating at capacity. Gracing those storied slips were some of Florida’s best Merritt, Monterey and Rybovich boats of the day, and home to some of the finest captains at the top of their game, such as Gary Stuve, the Stanczyks and Wink Doerzbacher. It hosted close to 10 North Carolina boats and numerous charter boats, as well as sport boats from Texas, and the good fishing continued.

Lima and his band of curators had an established fishery and a place to tie up — but knew if they weren’t careful they wouldn’t have it for very long, because having that many hooks in the hands of Hall of Fame crews armed with the latest in technology was bound to take its toll. They were adamant when it came to conservation, so taking measures to preserve the resource, in an attempt to avert mortal consequences to their sailfish population, was a necessity. The future of Isla Mujeres depended on them.

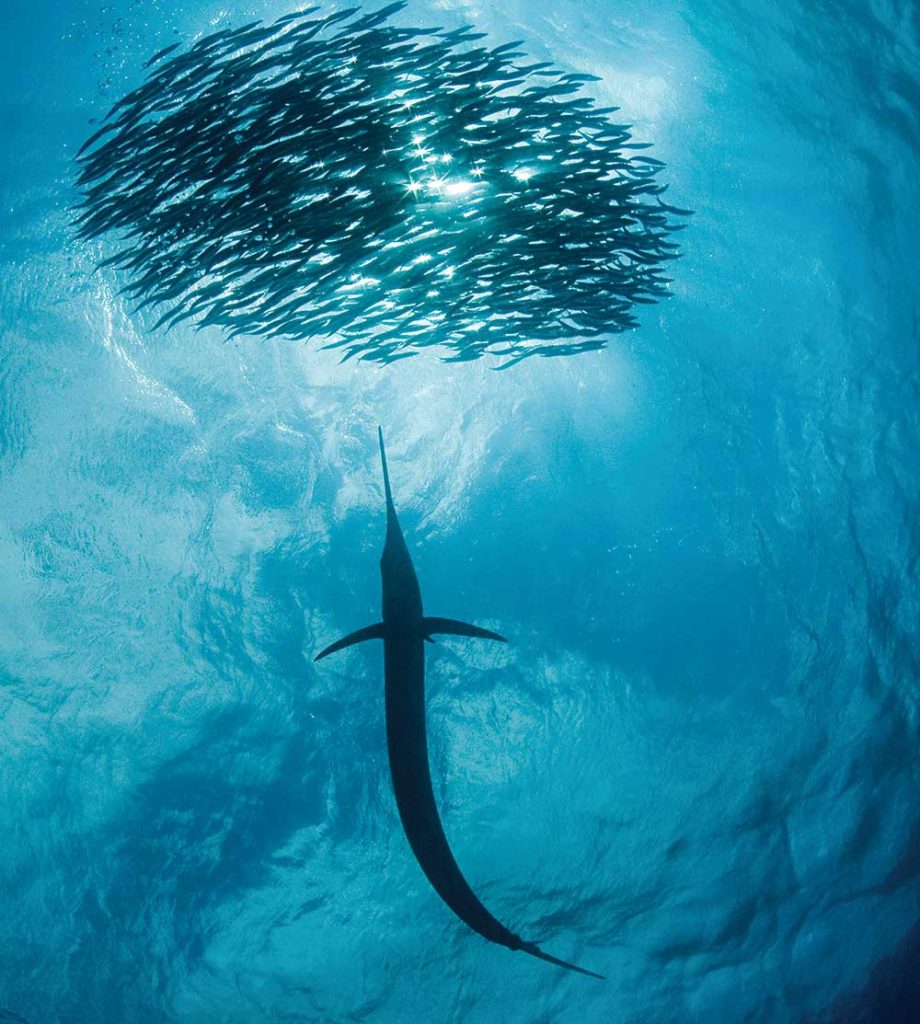

There is an entire set of rules when it comes to fishing this part of the Yucatan, some of which I think you can actually get in written form, but only from Lima himself. He still graces his marina every day and loves to share the local history with others. To successfully fish Isla, it basically comes down to this: absolutely no live-baiting of any kind, always take your turn on the baitballs and, please, no flag-flying.

“Sometimes order is called for,” Mendillo says. “And even though some of the rules are still questioned, it helps if the younger generation of fishermen is caught up on the ancient history, so they can make sense of them. After all, Isla Mujeres and its past have shaped today’s modern fisheries as much as it has shaped its own.”

If you respect the locals and show some sportsmanship, they’ll go to any lengths to help you out; disrespect them or their customs, and it’s buena suerte, amigo — you’ll be fighting bonitos until your arms fall off. Sportsmanship is a big part of the legacy that is Isla Mujeres.

Connecting with Isla’s Marine Life

To ensure year-round work for his charter-fleet crew and plenty of activities for visitors, Mendillo adjusts his charters accordingly. Not only does the Keen M operation take people sailfishing in the winter, they also take noted photographers — or anyone who is interested — to swim with the sailfish in the baitballs.

During the spring and summer months, the swim du jour might be with a docile whale shark, majestic giant manta rays or, for the adrenaline junkie: a shark-caged dip with the makos that also frequent this corner of the Caribbean.