Everyone’s got a story. This one begins in Vineland, New Jersey, some 40 years ago. Dominick LaCombe Sr., president of American Custom Yachts, continues to live the quintessential American dream: Make it happen for yourself, or wait for it to happen to you—which, as we know, is a strategy that hardly ever works. His journey from South Jersey to Stuart, Florida, is interwoven with the tale of a little boat named Glass Machine.

At the age of 10, LaCombe was put behind the wheel of his maternal grandfather’s boat. His grandfather was a merchant mariner, in the Navy, and eventually the U.S. Coast Guard. Who better to teach him? After all, the stripers were biting, and someone had to drive.

LaCombe’s father and paternal grandfather were landlocked upholsterers who did the occasional canvas job for boatbuilders such as Post, Egg Harbor and Pacemaker. They also enjoyed fishing, and getting young Dom out of school early on Fridays to head down the shore was never a problem.

Both grandfathers were the biggest influences on the career path LaCombe eventually would follow, and little did he know, after burning up two 283 and 327 Chevys and two 318 Chryslers on his grandfather’s 30-foot Owens by the ripe age of 15, that he would parlay his experiences into a life of boatbuilding. Sure, he loved boats, but it was the building—the fabricating—that set him on a course to leading one of the most advanced boatbuilding companies at the age of 29. The kid who would be running the fastest boat on the East Coast tournament circuit in 1984 soon learned that he could fabricate and customize anything. And while his hands did the fabricating, in his heart he was always a fisherman.

Cape May Summers

LaCombe’s first professional fishing job was working for the Castellini family, who owned a 47 Pacemaker, then a 45 Hatteras. There was no mate and the Castellini kids helped him do everything that needed to be done. He had a real knack for working with his hands and knowing the ins and outs of engines, so he was more to them than just a boat driver. He was trusted to work on all the expensive items—including mechanical systems, paint and upholstery—and was an invaluable asset.

Three slips down, Henry Tamani watched LaCombe from the bridge of his 38-foot Hatteras. He liked what he saw, but he was just starting to get into offshore fishing. LaCombe had freelanced for him the previous season, showing him how to fish the offshore canyons. And once the billfish bug bit Tamani, he was fishing like a maniac—leaving at midnight and staying out for two days straight. He wanted to do more, but his 38 wasn’t cutting it—so he bought a new 46 Hatteras and hired a captain.

One day, out of the blue, Tamani told LaCombe he was thinking of buying a 58-foot Monterey—a little-known boat that was built in Stuart.

“How’d you like to run it?” he asked LaCombe, who, without hesitation, said yes. Tamani started the new build with his current captain, who was calling the shots. LaCombe waited.

“The boat hit a submerged object at full speed, punching a 1-foot-by-4-foot hole in the bottom. There was nothing the captain could do, so they beached the boat to avoid sinking entirely.”

Dammit, Delaware

Tamani’s 58-foot Monterey, Glass Machine, was born in early summer 1982. The boat was on the way up the coast to begin the tournament season, after which LaCombe would take over. He was to take Glass Machine back to Florida and set up shop as a charter boat, sailing out of Sailfish Marina in Palm Beach. Tamani’s captain, who was fishing the boat out of Cape May, New Jersey, for the summer, was leaving after the final tournament of the season. Then disaster struck.

The Glass Machine teammates had the tournament in the bag—if they got back to the dock on time. They were running north from Virginia, and by the time they got to Delaware, they were much too close to the beach. Time was running out, and the weather was less than calm. The boat hit a submerged object at full speed, punching a 1-foot-by-4-foot hole in the bottom. There was nothing the captain could do, so they beached the boat to avoid sinking entirely.

Back in Cape May, it was getting late, and there was no Glass Machine. The rumors were flying, and the only real report was from the radio: The Glass Machine is taking on water. LaCombe was mating on a Bertram 42 in the tournament when he heard the rumor, and Henry’s wife, Diane, was pacing the dock, obviously concerned her husband and son weren’t back yet.

By 6 p.m., the confirmation came by single-sideband: Everyone is fine, but the boat is up on the beach. Unable to get hold of Tamani, LaCombe piled into his truck at 1 a.m. and drove to Rehoboth, Delaware, where he found the brand-new Glass Machine getting clobbered by the surf. By the looks of it, the boat must have hit a piling, but then he noticed a scratch that was made by something metal.

LaCombe later asked Tamani’s son, Henry Jr., “So, how close were you to the beach?”

“You could spit on it,” he replied.

The Recovery Attempt

The beach was steep and the back of the boat was in the water at high tide. Tamani wanted to salvage the boat, so the team brought in two Caterpillar D8 bulldozers with winches in an attempt to pull the boat up onto the dry sand; they wanted to get Glass Machine loaded on a trailer and on the road south to Florida for repairs. Although buckets of sand were being excavated by the bulldozers, it wasn’t working.

Tamani was determined to help, much to LaCombe’s disapproval. “We were trying to get the straps around the boat,” LaCombe recalls, “when a huge wave broke into the cockpit and threw both of us against the bulkhead. I held onto the covering board, but when the water receded, Henry was gone. Everyone panicked.”

Luckily for Tamani, he brushed by one of the divers on his way out with the wave, and he grabbed on to him.

“If the diver hadn’t been there, I wouldn’t be telling this story today,” LaCombe says.

For three days, the problem worsened. The sand was coming in with each wave, and with no way to properly patch the hole, the boat began heeling over with just the bow bobbing up and down in the surf. As the chines began to crack, the writing was on the wall: Recovery was becoming hopeless and a full-on salvage was imminent.

LaCombe quickly commissioned the help of the late Bobby Shomo of Johnson and Towers.

“We had the underwater torch, so we began stripping the boat,” LaCombe says. Off came the outriggers, then the shafts to try to save the engines. The last plan of attack was to abandon the mission altogether and get the hell out of Dodge; the word was out and the Environmental Protection Agency was on the case.

“There I am, a speed junkie who quit his job, watching my fast boat’s demise, and seeing the oil slick form and slink out to sea,” LaCombe says. Helicopters and small planes were flying over each day, and he knew it was only a matter of time until the EPA tracked that slick right back to Glass Machine.

If the government had its way, someone was going to pay for this disaster. As LaCombe and Tamani discussed a solution, they made the decision to sell the boat as soon as possible, because once the EPA had them in its clutches, the fine it would slap on Tamani would be infinitely more than the boat’s current value, which was pretty much nothing.

By noon, LaCombe had convinced the recovery foreman to buy the boat. While Tamani was in deep conversation with his lawyers attempting to draw up a sales contract, LaCombe stood by tapping his foot—and a helicopter was homing in on Glass Machine.

Knowing they were busted, LaCombe thought to himself: “Screw it, we can’t wait for lawyers.” He scribbled the primitive contract on what could just as well have been a cocktail napkin. The foreman signed it, purchasing the crippled boat for exactly $1—an hour and a half before a truck full of government officials drove right up onto the beach, heading straight toward the stricken vessel.

Glass Machine, Take Two

The glass bottle business must have been good in 1982, because shortly after the sale, Tamani called LaCombe.

“Dom, I’m thinking about buying Monterey,” he said.

“Okay,” was all LaCombe could muster.

“I want you to go there and build a new boat,” Tamani added. “I loved that one and I want another just like it.”

Now, LaCombe was more of a mechanic; he’d never actually built a boat before. On the way to Florida, he started thinking about how beautiful she was, that there must be men in their 50s and 60s—real craftsmen—building such fine-looking products. But once he arrived at the yard, he noticed that each of the workers were all young men around his age.

Trying to figure out where to start, LaCombe noticed an unfinished 63-foot wood hull sitting in the side yard. In the early 1980s, a 63 was thought to be too big for fishing. He called Tamani anyway and suggested they finish the 63 instead of starting another 58 from scratch.

“It’s too big,” Tamani said.

“No, it is not too big,” LaCombe replied, matter-of-factly. “The hull is already started, it will save us time, and you ought to have the biggest, fastest boat there is. Let’s make this 63 the flagship of the new Monterey Marine.”

The silence on the other end of the line made him nervous.

“But how are we gonna make it go fast?” Tamani finally asked.

“Leave that to me,” answered LaCombe, who had a driving desire to have the fastest boat on the East Coast.

It was 1983, and LaCombe was living in a trailer on the property, building the boat a few miles from the original shop on Monterey Road, in a pole barn next to the dump off Highway 714. Working day and night, seven days a week until midnight, and enlisting as many guys as he could to help finish the project, the boat was delivered in six months.

The bigger and better Glass Machine was outfitted with 1292 Detroits and dry-weighed in somewhere around 60,000 pounds. Once the project was completed in May 1984, LaCombe started the trip up the coast with plans to fish every tournament from Cape May to Cancun, showing off Tamani’s Monterey flagship 63.

“Let’s show these North Carolina boys what this Florida boat can do.”

The night before the Big Rock Tournament, Glass Machine arrived in Morehead City, North Carolina. The next morning, it was blowing like hell and the boats were staged at the inlet, waiting for the opportunity to head out. As Glass Machine idled around the corner, the fleet started the 10-knot jog out of the channel. On one side of LaCombe sat his mechanic, Glenn Hoff, and Monterey’s future general manager, Kenny Russell, on the other. LaCombe looked at them and said, “Let’s show these North Carolina boys what this Florida boat can do.”

He pushed up the throttles after the last Carolina boat cleared the channel, maintaining a steady 19 knots in the head sea. Glass Machine blew by everyone, spray flying.

Speed Sells

LaCombe was steadily promoting his demo boat, but wide-open throttle was selling it. Normal midnight departures from Cape May to the canyons changed to daybreak, and it wasn’t uncommon to find him fishing south along the North Carolina/Virginia border, then running back to Cape May in the evening.

As the fleet headed east, Lacombe pointed the boat south. “Wonder where he’s going today?” cracked the VHF.

“Here he comes…there he goes,” the captains said as Glass Machine flew past them.

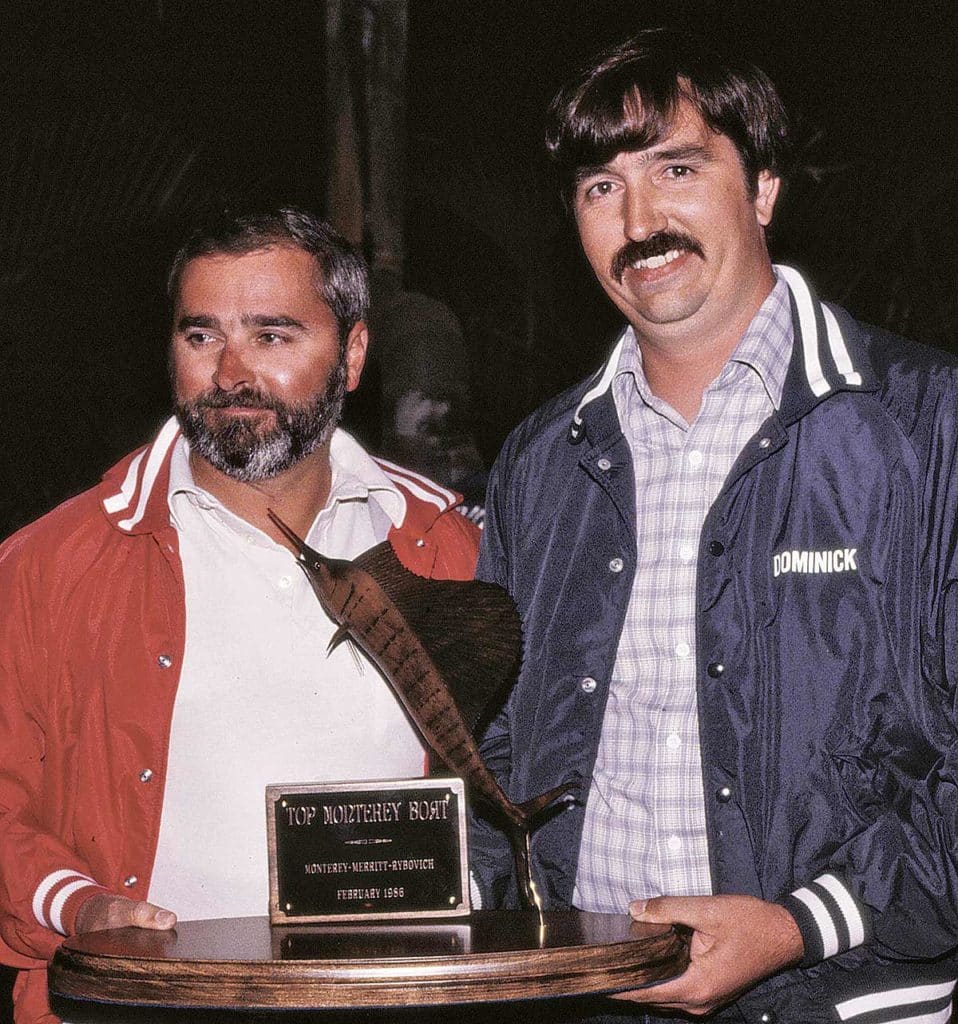

With the Northeast circuit winding down, the Rudee Inlet tournament was next on the schedule. The kickoff was in full swing as LaCombe waited his turn at the registration table. “Name of your boat, please?” the tournament official asked.

“Glass Machine,” LaCombe said quietly.

Captains standing within earshot rushed over to him. “Were you running the boat out the inlet on the first day of the Big Rock?” they asked.

“Yes, I was,” he answered.

The group was stunned. “We’ve never seen anything like that before,” they said.

The boat fished well, and they won a few tournaments that year, but LaCombe’s proudest moments were when he showed what the boat could do. At that time, there was nothing like it. Fifteen to 18 knots was the norm for the boats of the day, and the new Hatteras with Detroit 1692s was thought to be at the top of the game. But the radar gun that accompanied every single Glass Machine sea trial told a different story: 36 knots. All. Day.

Read our review of the American Custom Yachts build, Double Take.

The Next Chapter

LaCombe put 900 hours on the boat in the first six months, and he had lived up to his word by delivering Tamani the boat of his dreams—all 63 feet of her.

There had never been a sport-fisher that could run that fast, and a year after the boat was delivered, LaCombe received another life-changing phone call from Tamani: “Dom, I’m wondering if you’d be interested in running the company?”

LaCombe never gave that a single thought—every moment of the past year had been about Glass Machine—but if Tamani believed he was the man for the job, then he was. He returned to Stuart and connected with Billy Knowles, who was running Monterey in Tamani’s absence; Knowles’ son, who had been working at Rybovich, joined the team soon after. When it was all said and done, the man who never fancied himself a boatbuilder built 13 mind-blowing Montereys.

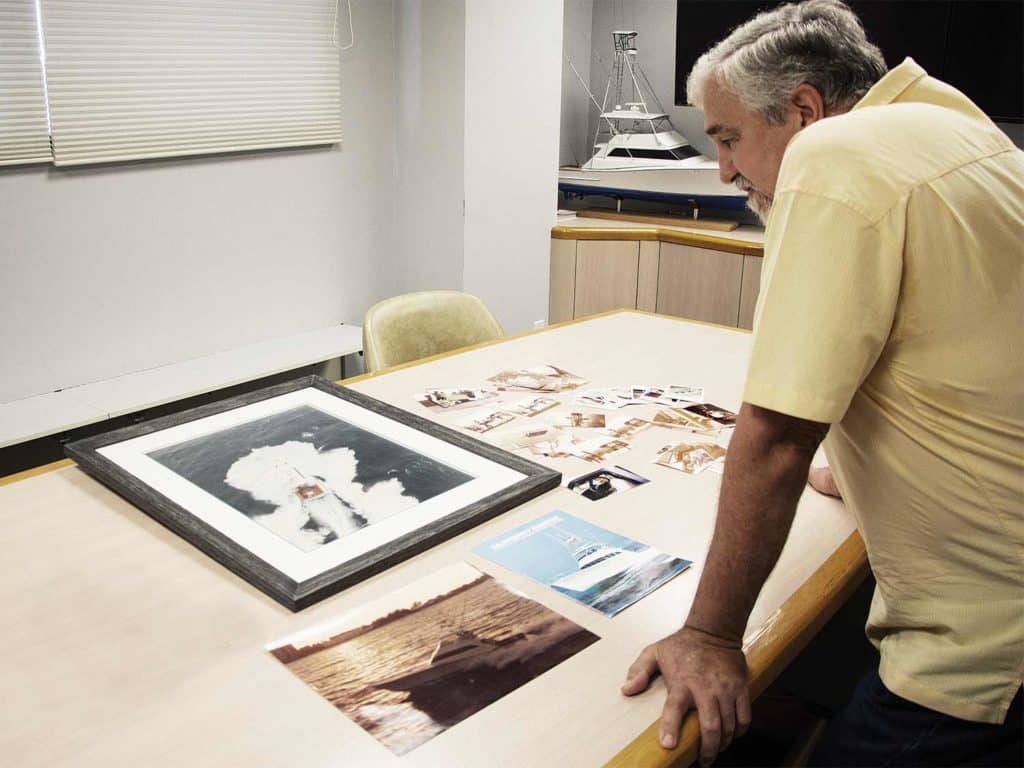

Many changes have occurred since then: Monterey Marine hasn’t been in business for quite some time, but the few boats that do surface on the fishing grounds are still turning heads, just like they always did. What started on Monterey Road in Stuart in the late 1970s continues to revolutionize the industry on Jack James Drive—where American Custom Yachts sits today.

Henry Tamani still lives in Stuart, and Dominick LaCombe Sr. still holds his Glass Machine memories close to his heart. Almost 40 years have passed since the two stepped onto that fabled beach in Delaware, not knowing what the future held.

Ask any veteran if he remembers the story of Glass Machine, and you’re likely to get an answer like this one: “How could you ever forget?”