Special delivery: Sign up for the free Marlin email newsletter. Subscribe to Marlin magazine and get a year of highly collectible, keepsake editions – plus access to the digital edition and archives.

The high-pitched screech of power tools sounds through the phone as Jon Duffie answers my call. “Hey, can I call you right back?” he asks. “I’m sanding a shower right now.” I quickly tell him to call me whenever it is most convenient for him. As we hang up the phone, I can almost feel the mist of fine fiberglass dust raining down around him. Minutes later, Duffie calls me from a quieter place, likely an office within his state-of-the-art workshop in Ocean City, Maryland. We jump into a conversation, and I get my first inside look at the man running Duffie Boatworks.

A relatively new addition to the boatbuilding industry, Duffie fits into a nebulous category of custom builders loosely considered to be the “next generation.” It’s tough to define what that even means because age and family history aren’t enough to draw the line between the original guild of boatbuilders and those who are considered new blood. Some next-generation builders are working in a family business, while others have started their own companies. Some started the business with financial security, while others got into the industry with different risks.

Though loosely defined, this group of custom builders also includes men such as Tim Winters, Cliff and Daniel Spencer, Alex Gill and Dusty Rybovich, John Bayliss Jr., John Floyd, and Ricky Scarborough Jr. Regardless of how they entered the industry, they’ve each stepped up to the plate out of sheer love and appreciation of boats and the hands-on craftsmanship it takes to build them.

A Legacy: Born to Build

When I called Ricky Scarborough to let him know that we’d be naming him as a next-generation builder, we both laughed at the idea. The most senior of the group, Scarborough hardly considers himself new to the game. And by all standards, he isn’t. He’d been building boats for decades alongside his father, Ricky Scarborough Sr., right up until the patriarch’s passing at the age of 73 in 2020, and he continues to build boats today under the family name. His next generation is now.

The Spencers, Gill, Rybovich, Bayliss and Floyd—all men who were either born into the business or brought up building it—still have their father-figure mentors close by. Sadly, Scarborough has lived through the loss of his. “He was the best father a boy could have,” Scarborough says softly, as he audibly chokes back tears. I tell him to take his time, and we pause for a moment. We share an aside and a quick laugh in a moment of levity, eventually circling back to Scarborough’s relationship with his father. “We were very close,” he says warmly. “He was 22 when I was born, and my mom and dad used to joke with me that we all grew up together.”

A name like Scarborough is one that is emboldened by legacy and often comes with a mix of perks and challenges. The next-gen boatbuilders whose fathers and grandfathers laid the foundation for their current successes don’t seem to showcase the stereotypical nepotism behaviors that we hear about so much in popular culture. “I know that I didn’t get here by myself,” Scarborough says. “When I was younger, I didn’t really think much about our family name and its legacy. My dad was just my dad, and he built boats. I thought that his work was cool and his boats were really pretty, but I can’t say that I ever thought of it any other way. I was blessed to have him as my father and to learn from him.”

And while blood might be the key to opening the door, it isn’t always easy to work with relatives. Nothing sets the stage for drama quite like a family business. The builders who follow in the footsteps of their elders work through disagreements, many of which often center on a founder’s unwillingness to change a process or technique, and his mentees’ eagerness to try something new. If you’ve argued with a family member about how to do something on a computer or smartphone, you can easily understand just how instantaneously your “help” can take a turn.

“Professionally, we all work very well together,” says Dusty Rybovich of his father, Michael, and brother Alex Gill at Michael Rybovich & Sons in Palm Beach Gardens, Florida. “Alex and I are constantly bouncing new ideas off our dad, and he’s right there to help us try them, or to show us why we shouldn’t. I won’t say that we never butt heads, but when we do, we’re quick to see where the other person is coming from and eventually come up with the best way to move forward together.”

Gill chimes in: “My dad is set in his ways. Our family has been doing this for 105 years, so he knows what works and what doesn’t. Even still, he’s gotten more flexible in recent years.”

Much like the others who are coming up under relatives, John Floyd and his uncle, F&S Boatworks founder Jim Floyd, put their family bond to the test when Floyd went to work for his uncle full time 10 years ago. “As it is with most folks, working with family has its pros and cons,” he says. “It’s nice because we have an intimate knowledge of how we operate and how we each think. But intimacy can lead to friction; some of it is generational, and some of it is just personality differences. My uncle is an old-school boatbuilder and has always been of the ‘if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it’ mindset, but today’s technology offers so many advantages that I’m constantly out here looking to make things more efficient with 3D printing and CNC fabrication.”

Although innovation can be trying for some, every next-gen builder I’ve spoken with outwardly recognizes the genius of their mentors. Do not mistake professional squabbles for signs of mutiny. They might disagree on certain approaches or innovations, but they know why their fathers or uncles have long been the face of the company.

“My dad is my hero,” says Cliff Spencer of his father, Paul. “He’s done right by our family, all while being an honest businessman too.”

Gill has similar admiration for his father. “My father is the head cheese,” he says. “Folks know that Dusty and I are in the mix too, but he is the face of the company. I’ve been to many boatyards in my life, and not one has an owner quite like him. The man mops the bathroom, mows the lawn, and trims the palm trees on the property every Sunday. This company is his life.” And it shows.

Floyd is also full of esteem and respect when discussing his mentor: “My uncle has forgotten more about carpentry and construction than I could hope to learn in two lifetimes.”

Like a Boss

There is no doubt that boatbuilders work extremely hard. They don’t often find a spare minute in their day, busy with handling customers, working through administrative tasks, or assisting with design and construction. Next-gen boatbuilders admittedly don’t always know just how much their mentors manage. Unpacking those responsibilities reveals a whole new appreciation for the work. “When I worked for my father, I learned how to do things,” Scarborough says. “When the business became my baby, I had to learn the why. Those things are just difficult to teach. It’s hard to tell someone in five minutes what has taken me 35 years to learn. So that was the most difficult part for me when transitioning into this role as the CEO and president. I knew how, but I didn’t always know why, and I’m still learning.”

A next-gen-builder role at a company is just about as murky as the category itself. Asking them to define their jobs was probably the most challenging question I posed. They self-described with words such as fireman, Renaissance man, jack-of-all-trades, carpenter, fabricator, welder, therapist and babysitter.

“We try to assign titles to each position at the shop,” John Bayliss Jr. says, “but the reality is that boatbuilding can be very unpredictable, and sometimes, we all end up wearing a lot of hats.”

Daniel Spencer concurs with Bayliss, adding: “I have no idea what my title is. I do a little bit of everything. Honestly, a title doesn’t matter to me.”

In family-legacy operations such as these, looking ahead can be tough. That’s not to say that they don’t have plans for the future or goals, but mapping out what to do following a patriarch’s departure can be painful and messy. “We don’t ever want the godfather to leave,” says Daniel Spencer when speaking of his dad. “He can’t ever retire. He’d be bored to death at home.”

Bayliss, whose father, John Sr., shares Paul Spencer’s impossible work ethic, also can’t imagine what the business would be like without its founder. “My dad has let me know that he will think about retiring when he reaches 120,” he says with a laugh, “so I guess we will be doing this together for a while. His shoes would be big ones to fill, and I still need a lifetime of knowledge and experience to catch up. I like being able to confidently bounce ideas and questions off him now.”

Scarborough, who unfortunately no longer has that sounding board, knows just how such transitions can be for legacy businesses. “The boss needs to have an exit strategy so that the transition is easier on everyone,” he says. “I hope that other builders have a clear, gradual transition plan that will help make things smooth for those involved, especially when the face of the company is leaving.” It’s a topic that no one wants to talk about when it comes to managing the smallest of assets or multimillion-dollar companies. It’s a difficult subject for any family.

Starting New

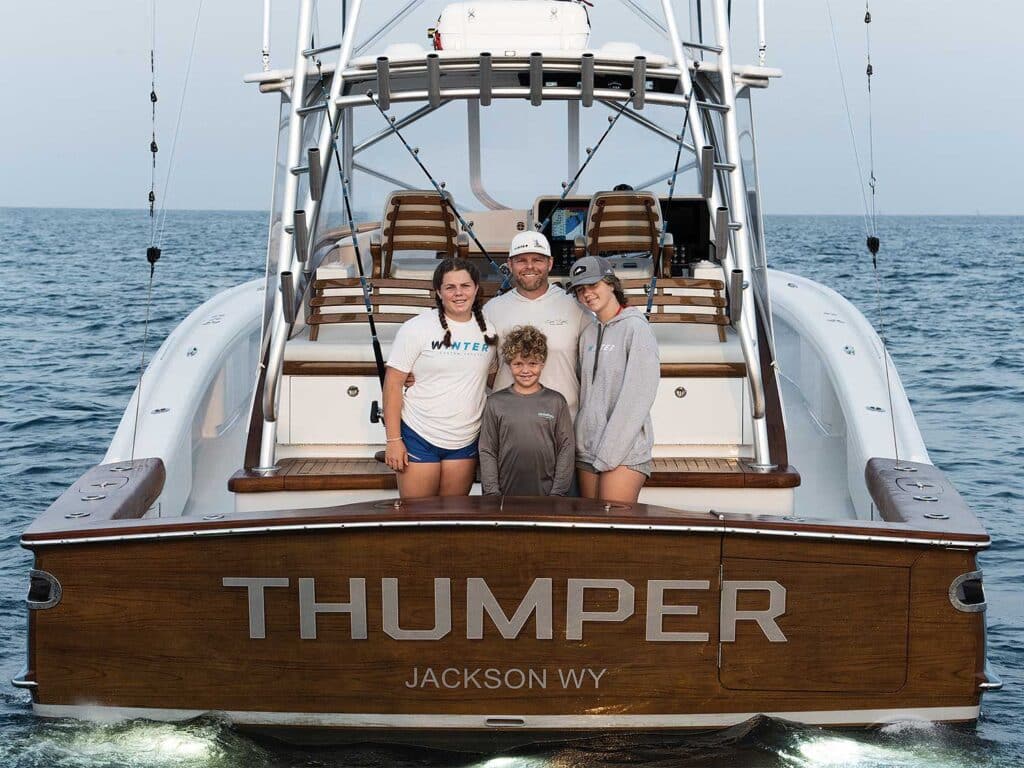

Builders such as Tim Winters of Winter Custom Yachts and Jon Duffie of Duffie Boatworks don’t have that legacy component to contend with just yet, but they both mentioned that it would be a real dream for them to see their children take over their companies in the future. “My son, Colt, loves drawing boats,” Duffie says. “He is eaten up with fishing already. I hope he takes over the business someday. That would be the ultimate dream.”

Ten-year-old Colt comes by this inclination honestly. Duffie grew up drawing boats too and still has the drafts to prove it. “When I was 12 years old, I was obsessed with Carolina boats,” he says. “I would draw every boat at the marina when we’d visit Oregon Inlet. I’d draw boats on scrap paper or the backs of place mats at restaurants. There’s a little bit of those drawings—and every boat I’ve ever loved—in the boats I build now.”

Duffie comes from a construction family, and it’s always been in his blood to build things. So, when he decided to pursue the boatbuilding venture, the family fully committed to his dream. By fishing on family-owned custom boats, he got to experience firsthand what he liked about each build, and what features or systems he’d like to modify.

Meanwhile, Winters, who happened to have that same dream, grew up in the Morehead City, North Carolina, area and worked in several different shops to get experience in the industry. His family had a cabinet shop, so he had a natural handle on carpentry already. After graduating from North Carolina State University with a mechanical-engineering degree, the young hopeful set out to start Winter Custom Yachts at just 20 years old.

Breaking into the business wasn’t easy for him. It was risky, especially without supplemental financial support or an established industry name. “I’m not afraid of taking risks,” Winters says. “This company was built on a hope and a prayer. I started my first boat without enough money to finish it, praying that someone would come along to fund it. We’ve been praying for 20 years, and we’re now on Hull No. 40.”

Although he’s got 20 years under his belt, Winters still battles unique challenges. Some consider him too young, and others hesitate to commit when they learn that he doesn’t come from a boatbuilding heritage. “I think all of us builders come from two different mantras: I’m trying to conquer the world, and others are under pressure to keep the world,” he says. “We’re coming from two different places, but I’m proud to be here with these guys. This is all I ever wanted to do.”

Shared Experiences

There is so much that sets these builders apart from one another, and yet several threads weave their storylines together. First and foremost, they are all deeply passionate about their craft and are steadfast believers in the finished products that they deliver to the owners. You could chalk that up to their knack for salesmanship, but I firmly feel that they really do believe that they’re each building the best boat available today. Oddly enough, I think that they all are correct in that opinion. There’s currently enough room in the industry for each of them to meet the unique demands of their customers. What one owner deems best might be entirely different for another, so each builder can continue to boast that their boats are indeed the finest of them all.

But to build those fine boats, they must also have a great team, a special family they get to work with each day. Even while grappling with challenges regarding demand, efficiency, workforce shortages, and changing technology, they still manage to build some of the world’s finest sportboats.

“I don’t have a single asset that is more valuable than my team,” Winters says.

Floyd adds: “I want to keep providing for the amazing family we have here at F&S Boatworks. Most have been here more than a decade, and others have been here since the first boat 25 years ago. We’re lucky to be surrounded by such an exceptional group of people.”

Surrounded by talented teams, these next-gen builders are taking the reins and charging ahead, each one sharing a common hope: that their companies will remain relevant over time. They’ll likely have to be adaptable as they plan for a different industry in the future. “When you look at how much time goes into building one of these boats, 10 years isn’t that long,” Dusty Rybovich says. “I don’t expect much to change in the industry over the next decade, but I do think that we’ll see major changes in the long run. Teak will become impossible to obtain; a few new gadgets and gizmos will come out that everyone must have; and I expect battery technology and marina infrastructure to advance far beyond what we see today.”

Read Next: Meet some of the talented craftsmen behind these incredible custom boats here.

These builders seem ready for a challenge, eager to learn and adapt to every innovation. Because ultimately, it’s all about helping an owner realize a dream and bring to life ideas that were once just scribbled on paper.

Whether they were born into it, helped to build it, or established the business themselves, every next-gen builder would likely acknowledge that their work is part of a greater story, a greater lineage of boatbuilding excellence that stretches well beyond any one man or one company. As promising leaders, this generation holds the future of custom boatbuilding in the palms of their well-worn hands, and we’re eager to see what they draw up next, perhaps with yet another new era of builders in tow.