Big-game fishing is a pursuit rife with tradition and time-proven tactics. In many ways, fishermen — a nongendered term that embraces both sexes — trust what we’ve learned over decades of personal experience and the experience of our mentors. Our mentality could be considered the opposite of today’s kids’ in relation to new technology. We are not early adopters.

That’s the environment marine propulsion engineers entered when they envisioned a new pod-drive system, a form of propulsion for boats that could change the way anglers pursue big game. Pods have taken certain segments of the cruising-boat market by storm, and now big-game charter captains who were once fixed-shaft aficionados are embracing this new technology.

A Brief History of Pod-Drives

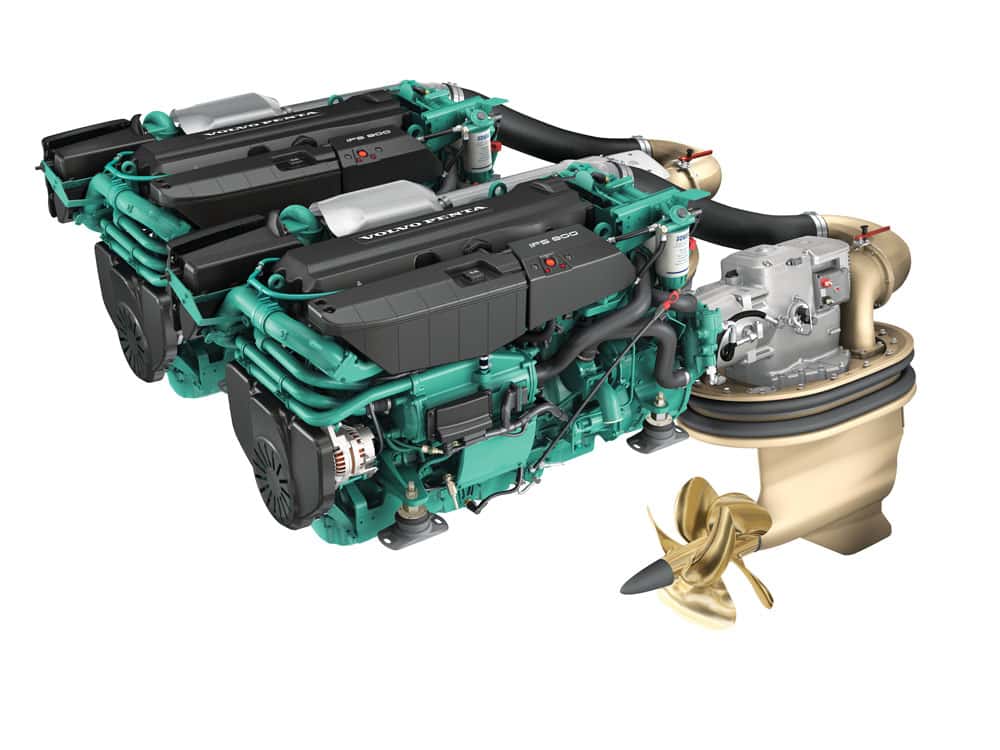

Volvo Penta introduced the first pod-drive system in 2004. The company didn’t invent them, but it made “pod” a household word among boaters.

The first pod-drive was invented in 1955 and went by the generic name “azimuth thruster.” They were either diesel- or electric-powered, and some were large enough for a man to walk around inside the machinery housing. Some had forward-facing propellers. Some could be rotated 180 degrees and run adequately facing either fore or aft. Interestingly, the most notable early prop-forward applications were in ice-breaking ships launched in 1990 — an interesting defense to the argument that forward-facing props were too vulnerable to debris.

Regardless of prop orientation, the first drives were a far cry from the watchlike beauties brought forth by Volvo Penta and, later, Zeus and ZF Marine.

When Volvo Penta took the industry by surprise with the IPS, it had patented the forward-facing counter-rotating propellers, patented new propellers for the design and also sent the exhaust out the back of the pod, not through the hub of the props. The new props don’t ventilate, and their position alignment with the keel gave them a decided advantage by leveling the keel on the hole shot.

At Volvo Penta’s IPS rollout in Mallorca de Palma, identical inboard and pod-drive boats were pitted against each other. The pod-drive boats were clearly more maneuverable and accelerated more quickly than strut, shaft and -prop-drive inboards.

First, hull efficiency was enhanced, because the props were always aligned with the direction of motion in the boat. Inboards’ props are angled downward, diminishing the power directed toward forward motion. Partly because of their angle of attack and partly because of their slightly forward position under the hull, pods gave more speed, better acceleration and more miles per gallon on the same horsepower.

Each pod turns independently of the other, giving remarkable maneuverability. By turning one engine pod at a sharper angle than the other in a turn, they could narrow its radius. By turning pods in opposite directions and running one in forward and one in reverse, the vessel can be pivoted more quickly and easily than in either outboards or inboards.

The most remarkable performance advantage was one that sent every propulsion and boatbuilding engineer to the drawing board to imitate: the joystick control system. With it, fingertip operation of any vessel became possible. Instead of having to jog throttles and shift levers to effect a maneuver, simply push, pull or twist the joystick and the boat follows the -directions, pivoting in place or crabbing sideways — say, into a slip that’s just long enough to fit your vessel.

One hardly noticed the greatest benefit to the end user: The engine systems were so compact, many boats could gain an aft cabin or at least a sleeping berth where diesel engines once thrummed away.

Pod Wars

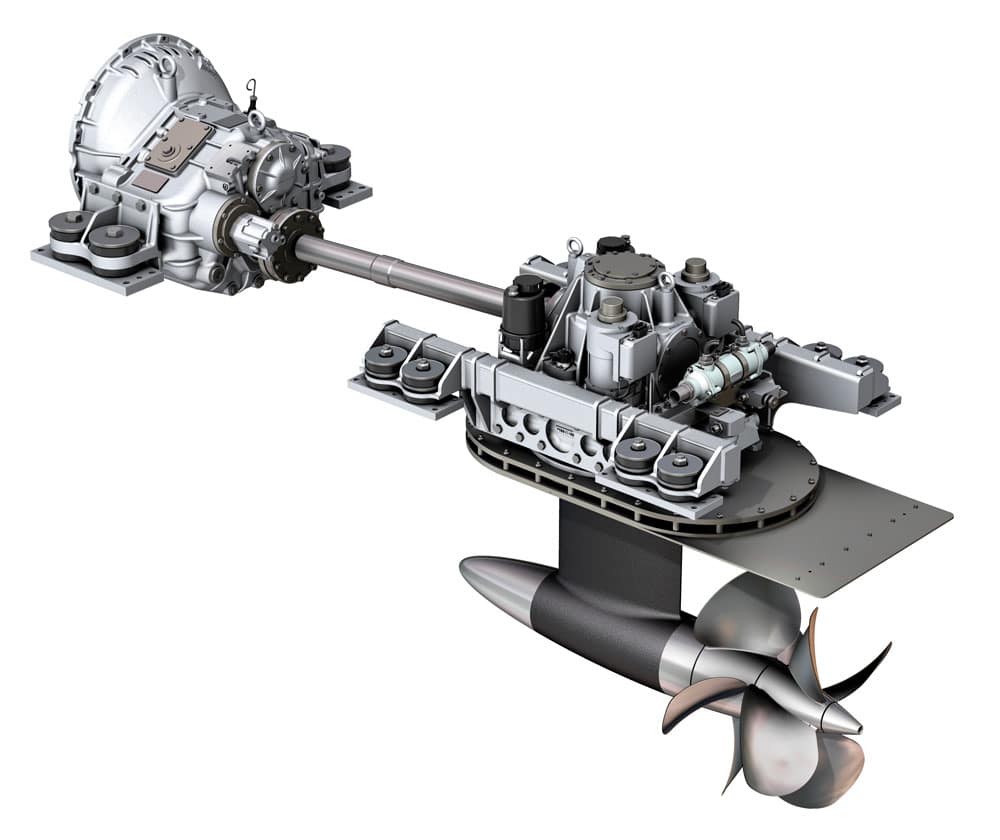

Months later, Mercruiser and Cummins joined forces to deliver Zeus pod-drives to boaters. They tasked ZF Marine to bring them a transmission that would mate with their Zeus pod, electronic controls and joystick steering.

However, the patent on forward-facing props — a feature that Volvo Penta claims gives its drives better “traction” by letting the broad blades and narrow hubs of their counter-rotating props turn in clean water well below the surface — was not utilized. Instead, Zeus pods came with traditional aft-facing props and the traditional exhaust-through-hub design. To get a good hole shot, Zeus countered with automatic trim tabs and matched the pods with tunnels to reduce draft.

And the Zeus pods also came with a joystick.

ZF Marine entered the pod fray when its exclusivity agreement with Zeus expired. Using a ZF transmission, it could mate any marine engine (Yanmar and Caterpillar have been popular partners) to its pods. ZF also built far larger pods that could handle far more horsepower. (Volvo Penta soon followed suit.)

ZF also added a trick that has less validity in the United States than in the European Union; ZF pods can be mated with both electric and diesel motors simultaneously, allowing them to run on electricity to meet the European Union’s emissions standards when in port.

While builders debated the benefits of the different pod designs, many new boaters were simply seduced by the joystick maneuvering system.

Then Zeus offered Sky Hook, a station-keeping device that combined data from a GPS and an electronic compass to keep the vessel perfectly still — within a yard or two. IPS followed with its own, and ZF ponied one up too.

It seems like this new tech gadgetry would have been off-putting to the salty captains, and it was, particularly among the sport-fisher crowds, who already had their docking and fish-fighting skills well honed.

Then Came Cat

Stephen Smith is the southwest sales representative for Caterpillar. He’s also got a lot of applications engineering in his background. You might not think of Cat as a pod company, but since ZF offered its pods to the market, he’s helped several manufacturers build ZF or Zeus pod with Caterpillar engines. Spencer Yachts builds an 87-footer with ZF pods, and Smith was integral to the development process.

“The maneuverability of the boat is what sells it, especially in close quarters,” he says. “The biggest fear boaters have is not about running out in the open water. It’s docking. With the joystick, my 12-year-old docks the boat.”

Another benefit comes from counter-rotating props on the pods.

“In standard shaft and prop boats, props lose their bite in close-quarters maneuvering,” Smith says. “Inboard props slip in both forward and reverse. But pod-drive engines use counter-rotating props. They bite hard and won’t let the engine spin up.”

Inboard fans argue that the pod-drives lack torque. And often, pods do have less torque than shaft-driven boats. Part of that comes as a side effect to the benefits of the prop’s angle of attack. It is so nearly parallel to the boat’s keel that it enables pod-drives to lighten the vessel with smaller engines that still provide ample thrust to plane and power the now lighter boat.

The downside is that a boat with less horsepower is more easily burdened by loading the boat. Gear, people, supplies, fuel and water lug a boat down, and the more it settles in the water, the more impact it has on your speed. In effect, a sport-fisher fresh out of the factory may make 45 knots on pods, but by the time it is provisioned and ready to fish, it’s going to lose some speed.

“Weight kills the speed on pod-drives, compared to shaft-drives,” Smith says. “When you put a pod system in, you try to do more with less.”

However, most sport-fishers rarely operate at wide-open throttle. Most studies show that maximum rpm only accounts for about 10 percent of the total running cycle of most boats and engines.

So how big is the pod market? Volvo Penta has 16,000 pod-drive boats in the marketplace right now. Zeus and ZF have only a few thousand pods in use.

Martin Meissner of ZF Marine says engine makers still don’t have a handle on the potential volume.

“That’s a hard question to answer, due to the past 15 months,” Meissner says, referring to the economic recession. “Our best guess is it will take a significant chunk of the market. But it’s also highly dependent on the application of the vessel. Pods are more prevalent in the pleasure-yacht category than in sport fishing. It’s hard to tell if sport fishermen will take to it. There are a lot of traditionalists in that market.”

“What customers are choosing is maneuverability. That’s the biggest attraction and why [pods] gained acceptance among a lot of enthusiasts, who wanted a certain size of vessel and want to move from a 28 to a 34 to 40 but were not comfortable with maneuvering inboard boats. Having the ability to move sideways, spin and dock raises the comfort level, especially for an inexperienced boater who wants to weekend but doesn’t want to train on an 18-foot vessel,” Meissner says.

“But in that case, it’s the ability to point and shoot that gives them comfort level. In that case, it’s not the pod; it’s our joystick-maneuvering system that does this, and we offer a joystick in a traditional shaft boat. You don’t have to redesign it to get our joystick maneuvering system. That’s opened up more opportunities and options for OEMS.”

In the beginning of pod development, there was a huge surge of interest. Most new boats developed in the 35- to 45-foot class were pods. But pods’ makers thought just a few years ago that one limiting factor of the pod market is speed. Trawlers don’t benefit much from pods. Their hull speed is usually 8 to 10 knots, and the power and efficiency of pods don’t kick in there much, even though they benefit from the added maneuverability, less vibration and less smoke.

International service is also a concern for pods. With a shaft and strut inboard, you can pretty much pull up to any marina in the world and get it serviced. They have shafts, they have props, and they can get more if they need them. Yet the pod makers are quickly closing that gap, and captains who have run them for several years indicate that the reliability has been very good.

“We have a strong global network,” says Robert Mirman of Cummins, who leads the charge for Zeus. “We back it up with a concierge service. If you aren’t happy with the local dealer, you can call the concierge and get a tech in Tennessee. That gives customers a stronger comfort level than an offshore service hotline.”

What Boatbuilders and Captains Say

Ariel Pared is the president of SeeVee, which has built about 20 Volvo Penta IPS-drive boats. “The IPS-drives fit well in our boats, and our owners love their maneuverability,” Pared says, and he has customers who can back up his word. Robin Buckley captains a SeeVee 39 with IPS 600s, named Kimbuktu.

“I was always an outboard guy,” he says. “I had one of the first triple-outboard SeeVees made, but I was sick of buying the gas, and Ariel was gonna try the IPS. We do a lot of high-speed trolling for wahoo at around 16 knots, and all the exhaust is under the water, so you don’t smell diesel fumes.”

He’s also found them to be extremely reliable.

“We had a few bugs in my first IPS boat. Sensors and things like that. But now that’s all gone away. I stay on top of the maintenance, oil and everything and never had a breakdown.”

Some people complain about the top-end speed of pods. While Buckley gets an impressive 50 mph with his pods, quad outboards would likely get another 5 to 10 mph. “But I usually run at 32 miles per hour and get 1.5 mpg,” he says. “With quad outboards, I’d get about 0.7 miles per gallon. With IPS I’ll run out to the Corner and fish the tide for wahoo, then head over to Gingerbread and get some yelloweye before heading home. I can do that on 200 gallons. That’s pretty good.”

Buckley also likes the IPS investment and isn’t concerned about the sticker shock. “It turns out that if I went with the new Cummins 550s and straight shafts, the IPS is a little cheaper.”

What else does he like about IPS?

“Sport-fish mode. It’s like a carnival ride. You put it in sport fish, and it locks the pods in opposite directions. Then with the joystick, it directs the transmissions to pivot or swivel. I can do a 180 in about a second and a half. It’s fun. It’s more maneuverable than an outboard, and you don’t have any engines on the back.”

Buckley dismisses the fear of forward-facing props.

“What if you do hit something?” he says. “You’re going to ruin more with a straight shaft than with IPS.”

In fact, shafts and struts have been driven through the hull by groundings and collisions with floating debris. Boats do sink from that very thing. Pods are designed to shear off without compromising hull integrity. And often, they are recoverable and repairable.

Grant Bentley captains Home Run, a 60-foot Spencer. He too is in love with the sport-fish mode and its maneuverability. “When you back down an inboard, the rudder posts start vibrating, and the boat sounds like it’s coming apart. Not on the pods. You get a little cavitation but nothing close to the noise from shaft-drives,” he says.

He gives even higher praise to the Clean Wake exhaust feature. “When I troll, I can turn it on and the exhaust bypasses the pod and comes out just above the water. It gets all the bubbles out of the wake,” he says. “They’re the cleanest-burning motors I’ve experienced. The transom stays clean and nobody is complaining of fumes.”

Capt. Todd Anderson recently ran a 50 Viking powered by ZF 4000 pods. He fished many tournaments with the boat, including the Mid-Atlantic at Cape May, the Pirates’ Cove tournament in North Carolina and several sailfish tournaments in south Florida.

Although he’s well versed in the care and maintenance of inboards, Anderson was still anxious to run a pod boat. “I liked the ZF right away. I’m all about new technology. I liked the idea of being able to handle the boat from the helm seat instead of standing up all the time. And, if you preferred to stand, Viking built the helm so you could control the pods with traditional dual levers.”

Anderson acknowledges that pods have advantages in some areas and disadvantages in others. “The engines are in their normal spot, but then you jackshaft to pods, so you lose space in the lazarette,” he says.

Some captains claim that the pods are too tall, requiring a higher deck to cover them. That could make billing a fish tough if you have to strain to reach the water. Todd pauses thoughtfully before answering: “We didn’t run into that problem.”

While nobody can predict the ultimate size of the pod market, as more and more people experience them, the polarity between love and hate is apt to change. “Right now, I can’t talk anybody who wants pod-drives out of them,” says Caterpillar’s Stephen Smith. “And if they don’t want them, I can’t talk them into it.”

Editor’s Note:

Regardless of the apparent belief that the pod-market growth spurt of the past nine years is over, several sources have reported that Caterpillar is preparing to release its own pod for 2014 — and Caterpillar isn’t denying it.