Special delivery: Sign up for the free Marlin email newsletter. Subscribe to Marlin magazine and get a year of highly collectible, keepsake editions – plus access to the digital edition and archives.

When Rapscallion’s charter guests finally arrived—hours behind schedule for a trip to Bimini—Capt. Larry Withall and his mate, Jason “Tiny” Walcott, disembarked from their slip in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, for a quick trip to the Bahamas in 1995. The two men chatted with Withall on the way out, asking various questions about the 65-foot Hatteras, seemingly interested in general safety procedures. They even asked what the crew would do in the case of piracy. Hours later, under a pitch-black sky, the guests suddenly stripped their friendly facades and brandished firearms. With a machine gun held to their heads, the Rapscallion crew realized that pirates were already on board.

When I think of pirates, I envision the likes of Capt. Jack Sparrow and other similar Hollywood characters. Fortunately, I’ve never had to contend with, or even consider, the threat of piracy at sea. However, after researching this article and speaking with seasoned captains who have experienced such incidents, my perspective has changed. While it might seem like a relic of a rum-drenched past, piracy is still a potential threat for sport-fishing crews and remains something to be prepared for today.

Modern-Day Piracy

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea’s abbreviated definition of “piracy” is “any illegal acts of violence or detention, or any act of depredation, committed for private ends by the crew or the passengers of a private ship or a private aircraft, and directed on the high seas, against another ship or aircraft, or against persons or property on board such ship or aircraft.” While that’s a lot of jargon, it can all be distilled simply to attacking or robbing ships at sea.

The International Maritime Bureau, a division of the International Chamber of Commerce, established its Piracy Reporting Centre in 1992 to assist with maritime safety. Following the United Nations’ definition of “piracy,” the center compiles data on piracy incidents around the world and publishes comprehensive reports. In addition, the nonprofit organization offers a 24-hour hotline for crews to report active attacks.

Acting as a single point of contact, staff will relay all the necessary information to the area’s proper authorities and warn other vessels in the vicinity. While much of its focus is on commercial shipping, the center also takes reports from other vessels, including fishing boats, yachts and other pleasure craft.

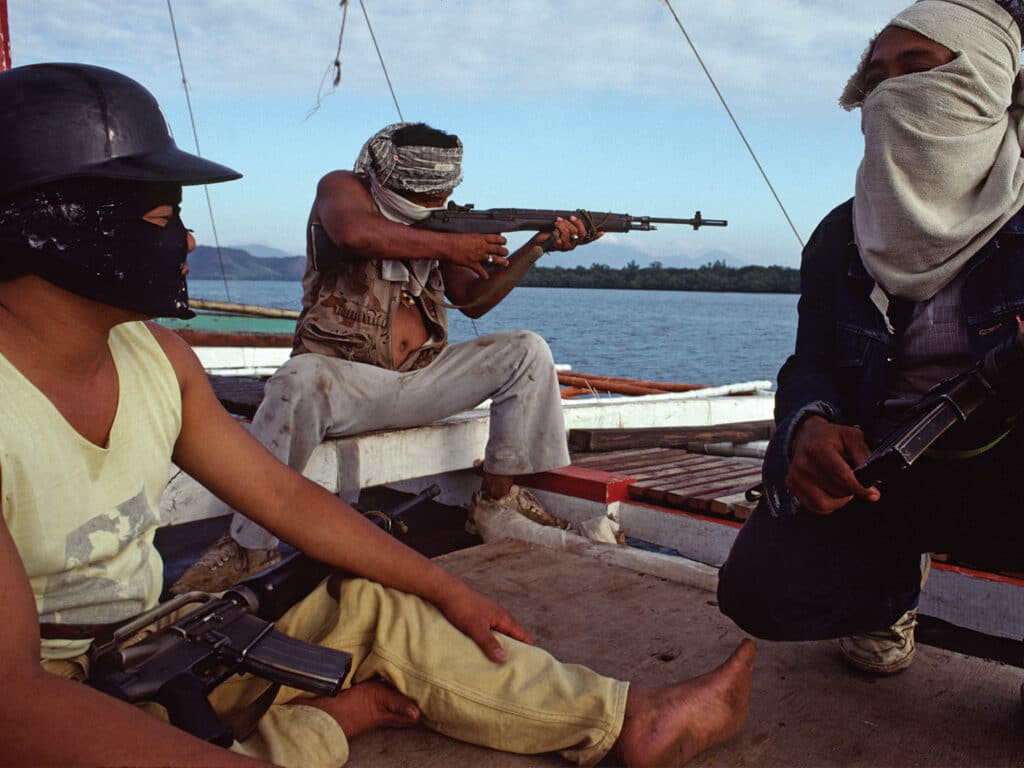

As of September 2023, 99 incidents had been reported for the year—a 10 percent increase from the year before. Of those, 53 incidents occurred in Southeast Asia, 23 in Africa, 18 in the Americas, three in the Indian sub-continent and two in East Asia. The Straits of Singapore, the Gulf of Guinea and the waters off Peru remain the three areas of greatest concern for the risk of piracy. While there are fishing programs that travel through those areas, the hotspots that I’ve heard the most about from captains and mates are in the Caribbean, such as the Bahamas, the British Virgin Islands and the Dominican Republic. Perhaps many of those close calls we hear about in casual conversation don’t get formally reported, or maybe they don’t quite meet the formal piracy definition outlined by the UN. Whatever the case, we still hear of them through social media and the coconut telegraph.

Hijacking at Sea

Whenever we hear of piracy incidents affecting sportboats, the haunting story of Rapscallion in the ’90s once again emerges from the sport-fishing community’s collective memory. Laced with emotional and physical terror, the hijacking of Rapscallion is the stuff of boating nightmares. Fortunately, both Withall and Walcott survived the attack. They were beaten and pistol-whipped and lived through scarring moments when they each thought the other was dead. After a series of movie-plot events, the then-23-year-old Walcott ran the boat aground at Gun Cay, an island 10 miles south of Bimini. When Rapscallion started taking on water, the pirates launched the life raft and fled.

Between the gunfire, fistfights, moments of titan strength, jumping ship, Apocalypse Now blaring in the background and split-second decisions, the hijacking of Rapscallion is the type of story that needs many pages of a book to tell it properly. Fortunately, Walcott is almost ready to publish one that has been nearly 30 years in the making. In the meantime, I encourage you to listen to Episode 71 of Dennis Friel’s Connected by Water podcast to hear Walcott’s detailed account of what happened. Withall and Walcott lived through one of our industry’s most notable piracy attacks, and their actions in a high-intensity situation helped them save each other’s life.

Withall, whom Walcott will always consider a brother and hero, sadly has passed away. Walcott, however, is very much active in the industry today. He’s worked on several boats over the last two decades and currently runs El Jefe, a 70-foot Viking that spends most of its time fishing off the Florida coast and in the Bahamas. There was a time when Walcott didn’t want to be defined by the Rapscallion story, but now, he cites the incident as being one of the most critical turning points in his life, and he discusses it with a tone of gratitude. “When I started fishing, I wanted to be good, but I didn’t take it that seriously,” he says. “After the hijacking, I had a new lease on life and recognized that I had to get serious about fishing if I wanted to make it a career. I found mentors in the likes of Ron Hamlin, Earle Keen, Larry Withall and Andy Moyes, and worked hard to learn from them and to compete with them. So really, the hijacking was the catalyst for my career growth and success.”

Practicing Situational Awareness

Since the incident, Walcott has learned some things about himself that likely contributed to his survival that night. He’s a fighter, and those instincts kicked in at a time when he needed them most. “I’ve had several close calls since the hijacking,” he says. “One incident even occurred in the same area years later. Just like in captains training, the first thing I do in an emergency is slow down. It’s like pulling back the reins on a wild animal, but you have to do it. I remain very calm when assessing and determining what to do next. I’m lucky to have great situational awareness.”

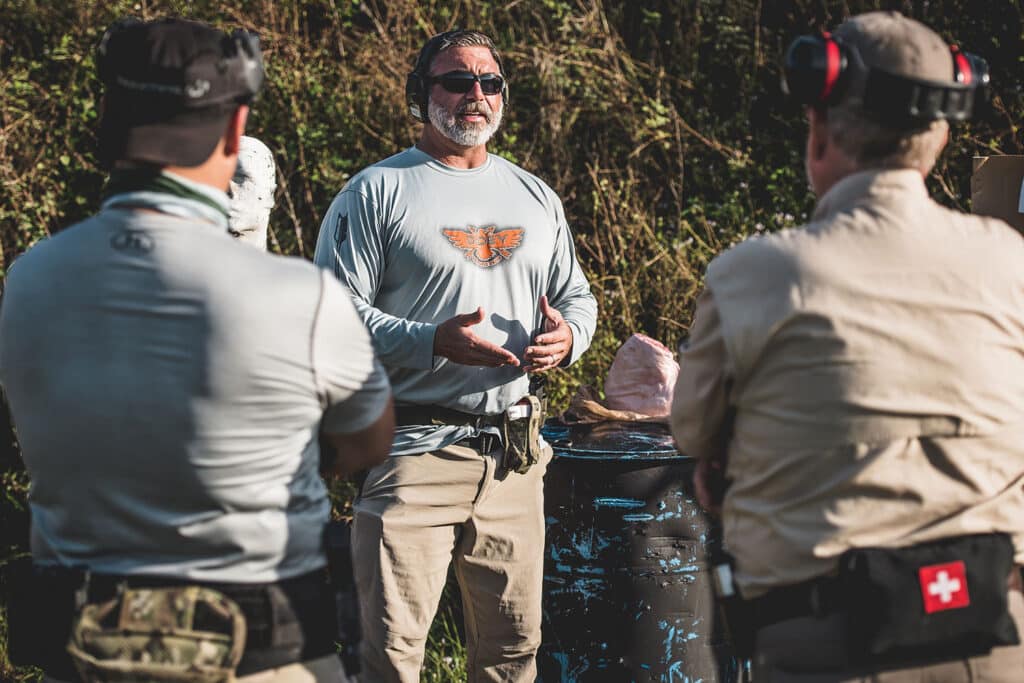

Situational awareness is the ability to comprehend and effectively respond to a situation by gathering information, analyzing it and making informed decisions to address potential risks. Men and women who work in high-intensity environments, such as police officers, military personnel and firemen, are extensively trained on situational awareness and how to pull back the reins, as Walcott describes. Don Deyo, a former Green Beret and medical expert who served in the US Army for 27 years, harps on this with the courses he offers through his company, D-Dey Offshore LLC. He’s worked with over 400 sport-fishing programs around the world to help them be prepared and outfitted for the worst. “The first level in preventing an incident such as piracy is simply paying attention to your surroundings,” he explains.

As a captain prepares for any trip offshore, it’s important to confront the fact that you might be on your own out there. Practicing situational awareness, even in low-pressure situations, will help you be better prepared for the unexpected. “I think that’s something bred into crewmembers—this idea that nobody is coming to save you,” Walcott says. “We know we have to be prepared for anything because no one else is coming to the rescue. Sometimes we have to be our own security on the water, so honing all of our skills, whether fishing- or safety-related, is never a waste of time.”

To best practice situational awareness, it’s helpful to know what to look out for, and there is no shortage of that information available from others in the industry. “Before you travel anywhere, you need to do your research of the area and ask around for information,” Walcott explains. Relying on their peers, captains can collect tips on areas to avoid, advice for communicating with authorities, and other helpful best practices.

Assuming that most pirates and other unsavory characters aren’t mining this article for insider tips, it’s helpful to recognize that a relatively clear pattern has emerged among incidents affecting sport-fishing vessels. Since these crimes are often opportunistic, pirates target boats that are anchored or chugging along slowly, especially those with a valuable tender in tow. “I will not pull a tender for that very reason,” says Capt. Cory Gillespie, who runs the 63-foot Titan Lunatico and spends much of the year traveling throughout the Caribbean. “I don’t fish when traveling either. I just want to get to my destination as quickly, efficiently and safely as possible.”

Two scenarios seem to be prevalent among piracy attempts targeting sportboats. First, a person on a small boat will call for aid from a nearby sport-fisherman by waving hands and holding a gas can in the air, a sign that perhaps they’ve run out of fuel. While I certainly don’t want to discourage folks from helping others, this has proved to be a ploy on many occasions. As soon as the vessel approaches to assist, the small boat suddenly picks up and runs directly at them, sometimes with additional perpetrators springing up out of nowhere. This tactic has been used several times at sea, and in some cases, the offenders had firearms at the ready. In the second scenario, a captain sees a boat—or several boats—on radar coming directly toward him at night, but none of the boats have any lights on. As they creep closer, the captain attempts to hail the vessels over the radio or shouts out to them without any response. The strangers continue to approach until they’re right on top of the sport-fisher and are close enough to suddenly launch an attack.

Using their instincts, crews who have run into such scenarios realized that something wasn’t right almost immediately. They managed to deter the threat by picking up and outrunning the small boats, proof that having a fast boat is indeed a safety benefit. In other cases, the crews showed the perpetrators that they had firearms at the ready. This brings us to a tremendously important and challenging question: Should you travel with firearms on board?

To Arm or Not to Arm

When I asked several prominent captains whether they travel with firearms, I received a variety of responses. Some said they always travel with guns on board, while a couple explained that they never felt the need. Others stated that they used to travel with firearms but eventually stopped after dealing with hurdles when declaring guns in other countries. When I asked whether captains traveling with firearms always declare them when clearing customs abroad, our discussions turned even more complicated and layered. The captains I casually polled were understandably squirrelly about all of this. Reveal too much, and suddenly you have a target on your back.

Onboard firearms are as much a legal consideration as they are a security one, and every country has its own regulations. Some require boats to turn firearms over when clearing customs. Others are more lenient. In addition, it’s not uncommon to get hustled or scammed, with officials withholding guns until they’ve lined their own pockets. Nevertheless, choosing to break the law and be dishonest about whether you have guns on board comes with some risks. “I have always declared my firearms,” Walcott says. “I have seen people get caught and spend months in jail. If you’re going to travel with guns, I strongly recommend you declare them. It’s not worth the hassle or risk for either the captain or the owner.” Capt. Trevor Cockle, who spent years of his long career running renowned boats such as The Hooker and The Madam, adds, “I’d rather take my chances without guns than deal with the consequences of shady officials. Although rare, such circumstances do occur, and I’d hate to have an owner deal with the consequences.”

As is the case with almost everything in this industry, the owner and captain need to agree on the firearms protocol before an emergency or traveling abroad. “My thoughts are that captains and owners need to have clear discussions about what the gun policy is going to be,” Cockle says. “Everybody has to be on the same page to avoid an owner ever receiving that dreaded call that there has been an incident and the boat has been impounded.”

While researching this article, it became very clear that being on the same page is especially critical for captains who are new to a program. When stepping into a new job, captains are busy learning the boat’s numerous systems as well as adjusting to new relationships with the owners. While the boat’s gun policy might not have been discussed during the interview, captains must know if there are guns on board and where they are stowed. In the rare event that the boat is boarded by law enforcement, the captain will need that information to avoid a potential problem—one that could potentially result in handcuffs.

Deyo encourages crews to evaluate which firearms are the most sensible choice for protection.

“Accompanied by extensive firearms training, I recommend folks have a semiautomatic rifle with a good scope for distance, a handgun and a shotgun,” Deyo says. “For those more comfortable with having a less-than-lethal option on board, a shotgun with pepper pellets could be a good fit. That said, if someone is trying to harm or kill you, I always like to point out that the less-than-lethal setup might not be the best choice. A rifle would likely be the most effective for deterring a threat at a distance and can be used to disable a motor. You must have experience with point of aim and point of impact when defending yourself on the water, so as always, training and practice are critical.”

In addition to the extensive medical kits and training offered by D-Dey Offshore LLC, Deyo’s company outfits boaters with full firearm setups that are practical for use on a boat. “Having a gun stuffed away in a cabinet or a drawer isn’t necessarily effective when you find yourself in an emergency,” Deyo says. “Preparedness prevents poor performance, so we offer personalized private fittings to outfit people with the appropriate weapons so they have what they need. For example, whenever we sell a boating customer a rifle, we also include the proper magazine, ammunition and a sling; with handguns, we provide customized gun belts with a retention holster. I’d recommend that crews keep their firearms on their person or within safe reach when crossing through areas that have a history of piracy incidents. Again, it’s all about being prepared.”

The choice to have firearms on board is an entirely personal one. On one hand, guns provide added security and might deter an attack. On the other, traveling internationally with weapons comes with inconveniences, as well as added responsibilities and risks. “You’re kind of damned if you do and damned if you don’t,” Gillespie says. “But whether you’re carrying guns or not, avoiding the incident is the primary goal. Rely on things like speed and range before jumping into a gunfight.”

Read Next: Learn more about reducing the risk of piracy from D-Dey’s Don Deyo.

“We didn’t have guns on board during the Rapscallion hijacking,” Walcott says. “If we did, the hijackers just would have had more guns. I firmly believe that firearms aren’t always the solution. It all depends on the situation.”

Since the hijacking, Walcott has become a sounding board for many other captains. “Lots of people have called me with bad gut feelings about charters,” he says. “They’d run the scenario by me, and I’d tell them to turn around.” He’s embraced his experience and hopes to use it to educate and prepare others. Working with military experts, he’s designing an anti-piracy training course for crews. “As captains and mates, we’re managing millions of dollars in assets and traveling around the world. We need to be educated and prepared with the proper training. At some point, you have to ask yourself, ‘What’s the price of my life?’”